Contact Hours: 3

This educational activity is credited for 3 contact hours at completion of the activity.

Course Purpose

To provide healthcare professionals with an overview of chronic pain and general treatment options.

Overview

Approximately 25% of the United States population suffers from chronic pain. Although chronic pain is a common ailment, it is often mismanaged, which can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. Because of its effects on morbidity and mortality, healthcare professionals must fully understand the diagnosis of chronic pain. This learning activity provides a review of chronic pain, its evaluation, and treatment options.

Objectives

Upon completion of the independent study, the learner will be able to:

- Define chronic pain

- Describe various approaches to evaluate chronic pain

- Review general options for managing chronic pain

- Review interprofessional team strategies for improving the treatment of chronic pain

Policy Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of FastCEForLess.com. If you want to review our policy, click here.

Disclosures

Fast CE For Less and its authors have no disclosures. There is no commercial support.

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.

Chronic Pain: A recurrent pain that lasts more than 3 to 6 months, which adversely affects a person’s well-being.

Inflammatory Pain: Refers to increased sensitivity due to the inflammatory response associated with tissue damage.

Mechanical Pain: Is any type of back pain caused by placing abnormal stress and strain on muscles of the vertebral column.

Musculoskeletal Pain: Pain that affects the muscles, ligaments and tendons, and bones.

Neuropathic Pain: Nerve pain that may occur because of a disease process.

Nociceptive Pain: Pain that is caused by tissue damage and injury.

Psychogenic Pain: Physical pain that is primarily caused by psychological factors.

An individual’s quality of life is affected by the management of chronic pain. Chronic pain is described as a recurrent pain that lasts more than 3 to 6 months, which adversely affects a person’s well-being. ³ There are multiple sources of chronic pain, and often, individuals diagnosed with chronic pain will complain of more than one type of pain. For instance, a person with chronic back pain may also have fibromyalgia. Likewise, a significant percentage of people with chronic pain also suffer from depression and anxiety. ¹⁵ Because of multiple modalities that are associated with pain, combination therapy that includes pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatments has shown to be effective in its management.

There are multiple categories and types of pain, including inflammatory, mechanical, musculoskeletal, neuropathic, nociceptive, and psychogenic pain. The following provides a brief overview of the pain types ³˒⁹˒¹¹:

Inflammatory Pain – Refers to increased sensitivity due to the inflammatory response associated with tissue damage. Examples include:

- Autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis

- Infection

Mechanical Pain – Is any type of back pain caused by placing abnormal stress and strain on muscles of the vertebral column. Examples include:

- Poor posture,

- Poorly designed seating

- Incorrect bending and lifting

Musculoskeletal Pain – Pain that affects the muscles, ligaments and tendons, and bones. Examples include:

- Back pain

- Myofascial pain

Neuropathic Pain – Nerve pain that may occur because of a disease process. Examples include:

- Peripheral neuropathic pain such as diabetic neuropathy

- Central neuropathic pain such as spinal cord injuries

Nociceptive Pain – Pain that is caused by tissue damage and injury. Examples include:

- Pain due to actual tissue injuries such as burns, bruises, or sprains

Psychogenic Pain – Physical pain that is primarily caused by psychological factors. Examples include:

- Headaches or abdominal pain caused by emotional, psychological, or behavioral factors

When obtaining a history and physical, the history should include the onset of pain, the location, whether the pain radiates, the quality, severity, and frequency of the pain, the occurrence of breakthrough pain, any factors that contribute to relief or worsening of the pain, and any mechanisms of injury that may have caused the pain to occur. ³ Also, associated symptoms should be assessed, such as muscle spasms or aches, temperature changes, restrictions to range of motion, morning stiffness, weakness, changes in muscle strength, and changes in sensation. ¹⁶

In addition to the pain symptoms, the impact of the pain on daily functions should be assessed, including a review of the activities of daily living. ³˒¹⁶ It is important to understand how chronic pain affects a person’s quality of life. When reviewing the impact of pain on quality of life, the healthcare professional should inquire the following:

- Is pain impacting relationships or hobbies?

- Does the individual find themself becoming depressed?

- Does the pain interrupt sleep patterns?

- Can the individual go to work without limitations?

- Are activities of daily living such as bathing, dressing, eating, or walking limited or restricted?

After obtaining a history of the pain, a detailed neurologic exam should be completed, as well as a physical exam that includes a thorough examination of the area of pain.

A pain scale is often a visual method that allows one to track their pain, its intensity, and other symptoms. These scales can be self-reported verbal rating scales, and can also be judged by behavioral or observation, especially in children and nonverbal adults. The following are various forms of pain scales often used by healthcare professionals to document pain. ¹⁶

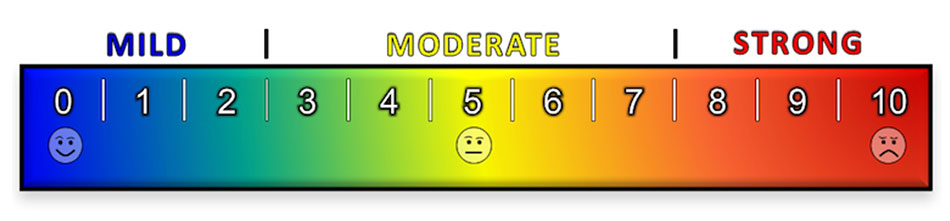

0-10 Pain Scale

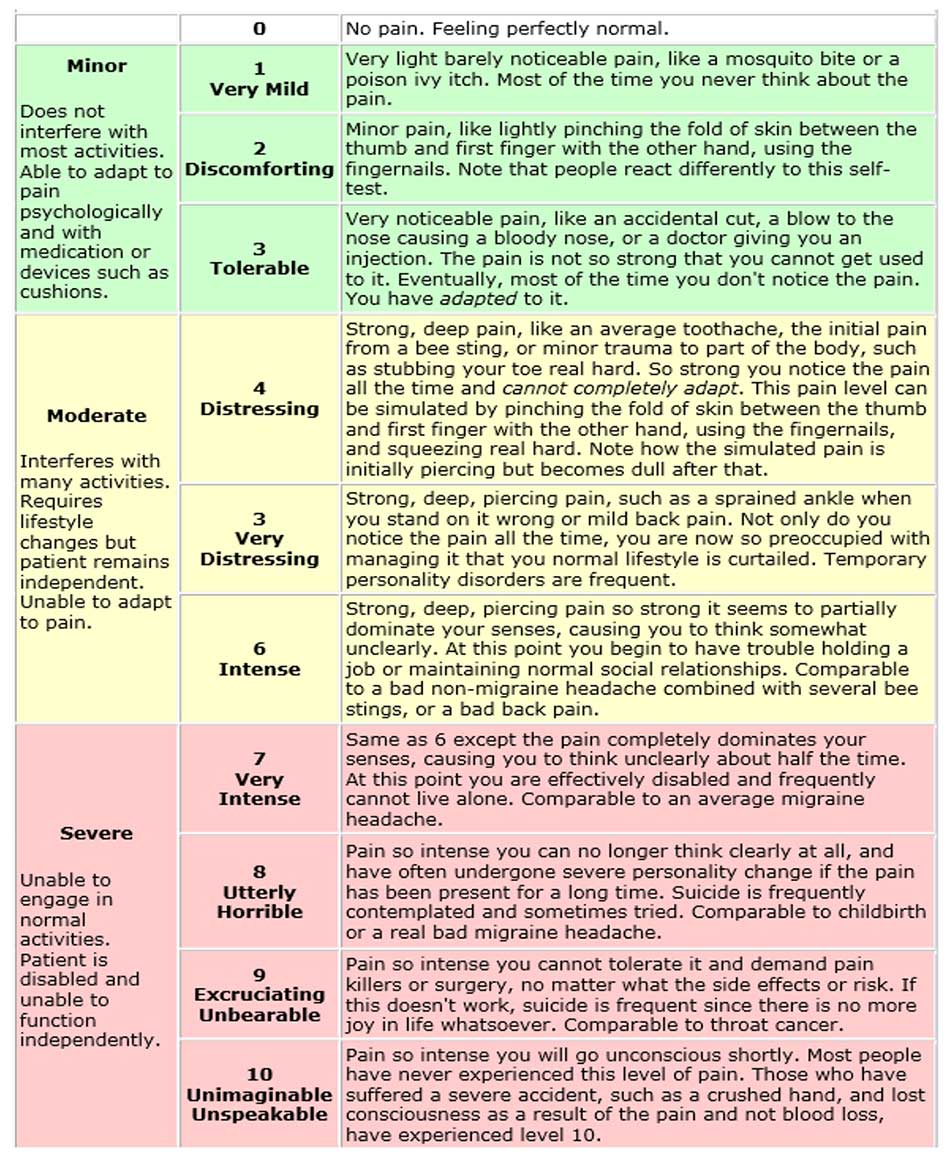

The 0-10 pain scale is the most used scale to assess for pain. This scale is simple and effective and works for many people, but it can be limiting to individuals who do not understand numerical order, or what each number represents. Also, the healthcare professionals understanding of a number associated with pain may be significantly different the person describing their pain. For instance, an individual may express pain being a “4”, and the healthcare provider may interpret the number “4” as being pain that is tolerable when it is not. The difficulty with the 1-10 pain scale is that it is subjective, both for the individual, and the healthcare professional. The Stanford Pain Scale from 0-10 is a good alternative to use in assessing pain and helps clarify subjectivity when an individual describes their pain.

The Stanford Pain Scale

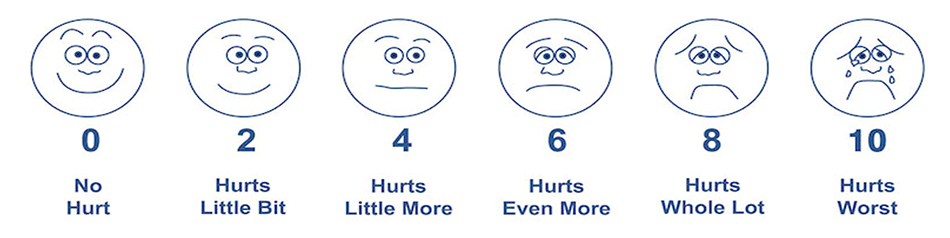

Wong-Baker FACES®

The Wong-Baker FACES pain scale is a reliable way to diagnose pain in children and nonverbal adults. It uses a zero to ten scale to judge pain and correlates facial expressions to the pain numbers. One disadvantage to this scale is that it may not be descriptive enough to assess pain and may not be helpful for those diagnosed with autism.

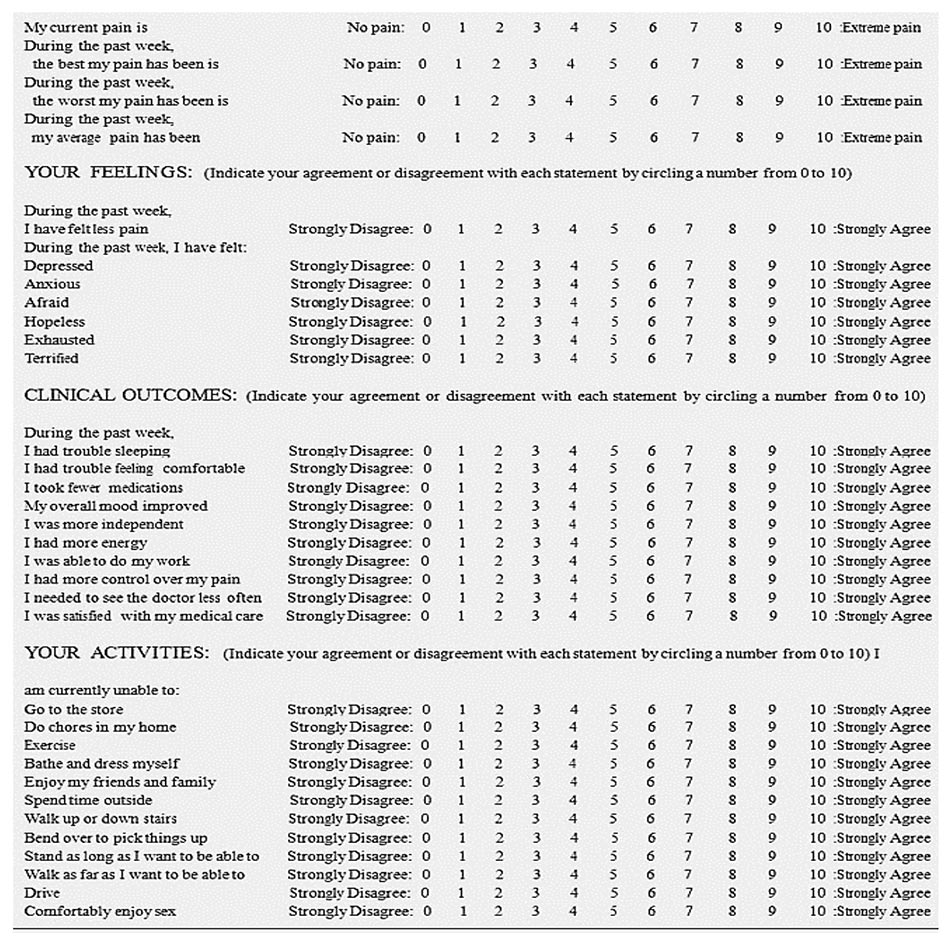

Global Pain Scale

The Global Pain scale is a diagnostic tool that focuses on physical pain and how that pain affects and individual’s life. Unlike numeric or visual analog scales, the global pain scale is a more thorough screening tool to assess:

- Ability to engage in activities of daily living

- Clinical outcomes

- Current pain levels

- Emotional well-being

- Pain status

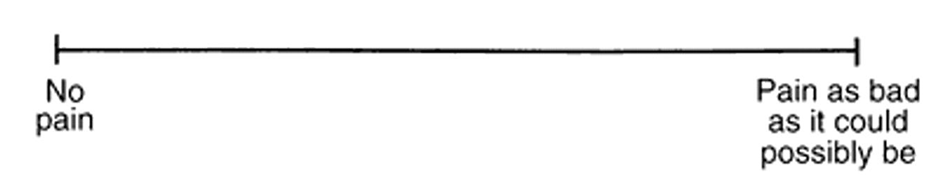

Visual Analog Scale

A Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is a scale used to determine a person’s intensity of pain that is experienced. It consists of a line that is approximately 10-15 cm in length, with the left side signifying no pain and the right side signifying the worst pain ever. The VAS recognizes that many people do not experience pain in discrete units like numbers, but in a variable way that exists on a sliding scale. A pain VAS allows patients to mark their pain intensity on a continuum. The elderly may need additional assistance when using this type of pain scale.

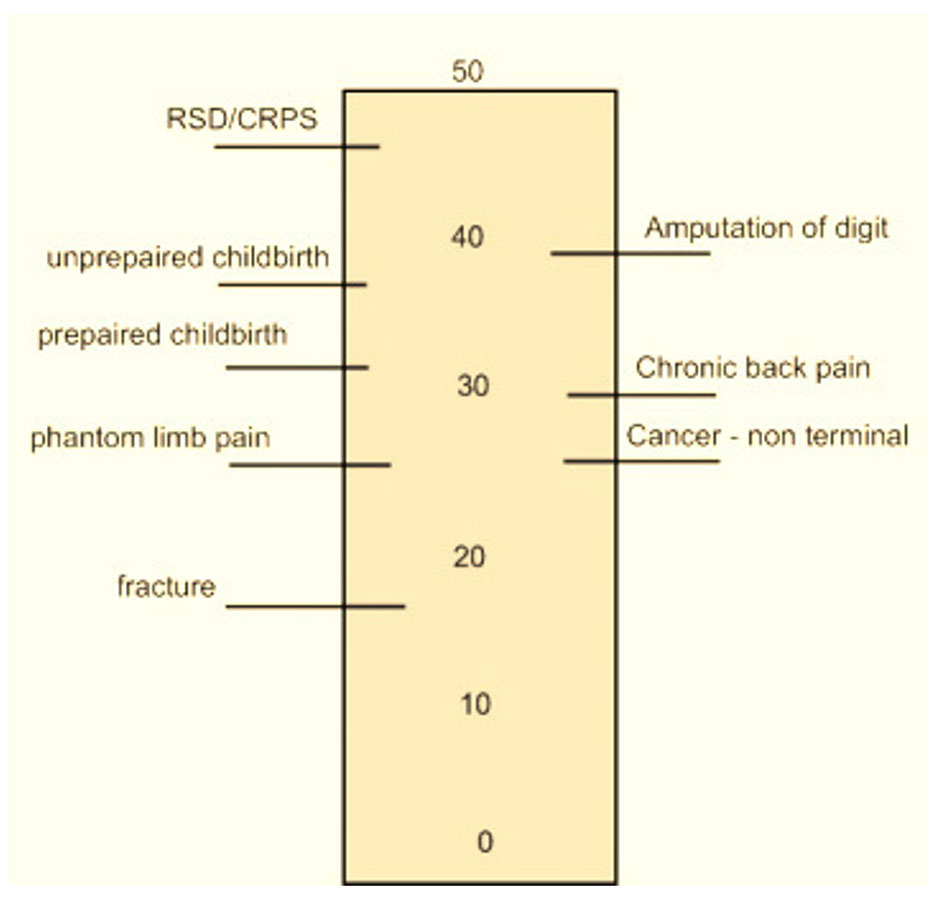

McGill Pain Index

The McGill pain index is used to measure complex regional pain syndrome. Instead of fixing pain intensity only to a number, it compares it to other injuries or types of pain to help quantify pain. The McGill pain index incorporate sensory qualities, affective qualities of pain, and evaluative issues to help pinpoint the intensity of pain.

Color Pain Scales

Color pain scales are a helpful way for children to judge their pain levels. The scale is usually shaped like a thermometer, with darker red colors indicating more pain.

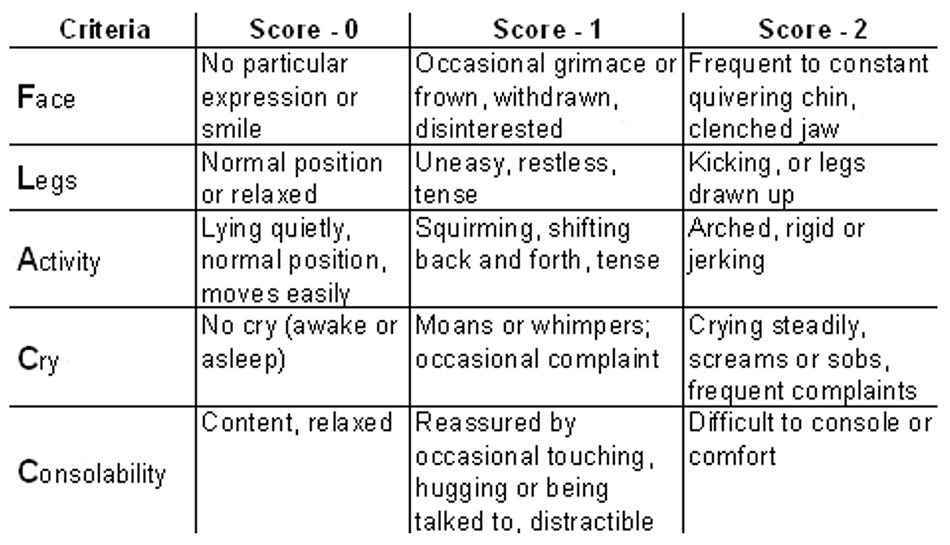

FLACC Scale

The face, legs, arms, cry, and consolability (FLACC) pain scale uses expression, leg movements, activity, crying, and consolability to categorize pain. It is often used to assess pain in children, but it is also a useful tool to assess pain in nonverbal adults.

Standard blood work and imaging are not indicated for chronic pain, but the healthcare professional can order it when specific causes of pain are suspected, and on a case-by-case basis.

Psychiatric disorders can increase pain making symptoms of pain worse. ²˒¹⁵ There are twice as many prescriptions for opioids prescribed each year to people with underlying pain and a comorbid psychiatric disorder compared to people without psychiatric disorders. Major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder are the most common comorbid conditions related to chronic pain and having such diagnoses can significantly delay the diagnosis of pain disorders. ²˒¹⁵ For example, an individual who suffers from depression may also complain of fatigue, sleep disturbance, and loss of appetite. Over time, these symptoms can make their pain worse. It is crucial to realize people with chronic pain are at an increased risk for suicide and suicidal ideation, ¹⁵and people with chronic pain should be screened for depression.

Current recommendations for chronic pain include referring an individual to pain management when the pain is debilitating and unresponsive to initial therapy. The pain may be located at multiple locations and require multimodal treatment or invasive procedures to control pain. ¹ Treatment of both pain and a comorbid psychiatric disorder leads to a more significant reduction of both pain and symptoms of the psychiatric disorder. ¹⁷ There are multiple pharmacological, adjunct, nonpharmacological, and interventional treatments for chronic, severe, and persistent pain.

The list of pharmacological options for chronic pain is extensive. This list includes nonopioid analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs), acetaminophen, and aspirin. Additionally, medications such as tramadol, opioids, antiepileptic drugs (gabapentin or pregabalin) can be useful. ¹³ Furthermore, antidepressants such as tricyclic antidepressants and SNRI’s, topical analgesics, muscle relaxers, N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonists, and alpha 2 adrenergic agonists are also possible pharmacological therapies. ¹³

- Acetaminophen: Used for mild-to-moderate pain, moderate to severe pain (as adjunctive therapy to opioids), and temporary reduction of fever. ¹˒¹³ The precise mechanism of action for acetaminophen is unclear. Acetaminophen lacks anti-inflammatory properties but does produce analgesia. If administered orally or rectally, acetaminophen may cause any of the following ¹⁷:

- Rash or hypersensitivity reactions

- Hematological reactions, such as anemia, leukopenia, neutropenia, pancytopenia

- Nephrotoxicity

- Metabolic and electrolyte disorders such as:

- Decreased serum bicarbonate

- Hyponatremia

- Hypocalcemia

- Hyperammonemia

- Hyperchloremia

- Hyperuricemia

- Hyperglycemia

- Hyperbilirubinemia

- Elevated alkaline phosphatase

If administered intravenously, side effects include nausea, vomiting, pruritus, constipation, and abdominal pain. For children, regardless of the route of administration, the most common adverse reactions are nausea, vomiting, agitation, constipation, pruritus, and atelectasis. ¹³

- Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs): Used for mild-to-moderate pain, pain associated with inflammation, and temporary reduction of fever. The primary mechanism of action is the inhibition of the cyclooxygenase enzyme, thereby inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis. ⁶ Drugs in this group are categorized according to chemical structure and selectivity: acetylated salicylates (aspirin), non-acetylated salicylates (diflunisal), propionic acids (ibuprofen, naproxen), acetic acids (indomethacin, diclofenac), anthranilic acids (meclofenamate, mefenamic acid), enolic acids (meloxicam, piroxicam), naphthylalanine (nabumetone), and selective COX-2 inhibitors (celecoxib, etoricoxib). Most NSAIDs inhibit both COX isoforms (COX-1 and COX-2) with little selectivity. ⁶ However, those that do bind with higher affinity to one or another (aspirin) will exert anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antipyretic effects at different degrees. For this reason, low doses of aspirin manifest an antiplatelet effect, while high doses exhibit an analgesic effect. Side effects of NSAIDS may include ⁶˒⁷:

- Gastrointestinal: Nausea, anorexia, dyspepsia, abdominal pain, ulcers, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, perforation, constipation, diarrhea

- Cardiovascular: Hypertension, decreased effectiveness of anti-hypertensive medications, myocardial infarction, stroke, and thromboembolic events, inhibit platelet activation, bruising, hemorrhage

- Renal: Salt and water retention, deterioration of kidney function, edema, decreased effectiveness of diuretic medications, decreased urate excretion, hyperkalemia, analgesic nephropathy

- Central nervous system: Headache, dizziness, vertigo, confusion, depression, lowering of seizure threshold, hyperventilation

- Hypersensitivity: Vasomotor rhinitis, asthma, urticaria, flushing, hypotension, shock.

- Hepatotoxicity

- Antidepressant medications: Selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), particularly duloxetine, and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), especially amitriptyline, have demonstrated usefulness in a variety of neuropathic pain conditions. Thus, they are recommended as the first line of treatment for neuropathic pain. ¹⁵ In addition, they are also indicated for fibromyalgia, psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, chronic musculoskeletal pain, and prophylactically for the treatment of migraine and tension-type headaches. Both SNRI and TCA pharmacological groups seem to be more effective in patients with depressive symptoms and pain as comorbidity than in those patients with pain alone. ²˒¹⁷ Both tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) inhibit the reuptake of two important neurotransmitters: serotonin and noradrenaline. This inhibition increases the descending inhibitory pathways of the central nervous system related to pain. Additionally, TCAs also act on cholinergic, histamine, beta2 adrenergic, opioid, and N-methyl-D- aspartate (NMDA) receptors, and sodium channels. Side effects include;

- Amitriptyline: Altered mental status, arrhythmias, constipation, decreased libido, dizziness, drowsiness, dry mouth, headache, hyperhidrosis, increased risk of suicidal thoughts, urinary retention, nausea, orthostatic hypotension, tremor, weight gain. ²˒¹⁵

- Duloxetine: Nausea, headache, dry mouth, somnolence, dizziness, abdominal pain, constipation increased blood pressure, increased risk of suicidal thoughts.

- Antiepileptic medications: Several antiepileptic drugs are also known for their analgesic properties through their mechanism of action of lowering neurotransmitter release or neuronal firing. The most common antiepileptics used for pain treatment are gabapentin and pregabalin. ¹³

- Gabapentin: Is often used for postherpetic neuralgia and neuropathic pain. The most common side effects are dizziness, somnolence, ataxia, peripheral edema, and confusion. Among other, more serious adverse effects are anaphylaxis, suicidality, depression, fever, infection, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, angioedema, erythema multiforme, and rhabdomyolysis.

- Pregabalin: Is used for neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, spinal cord injury, postherpetic neuralgia, and fibromyalgia. Side effects include dizziness, somnolence, headache, peripheral edema, nausea, weight gain, disorientation, blurred vision, increased risk of suicidal thoughts.

- Local Anesthetics: Lidocaine is one of the most used local anesthetics, which is used for postherpetic neuralgia and peripheral neuropathic pain. ⁵˒⁷ Lidocaine works by stabilizing the neuronal membrane by inhibiting sodium ion channels on the internal surface of nerve cell membranes, resulting in reduced impulses for pain. Side effects include pain at the application site, pruritus, erythema, and skin irritation.

- Opioids are considered a second-line treatment option for chronic pain. Their administration is usually recommended when alternative pain medications have not provided adequate pain relief or are contraindicated, as well as when pain is impacting the quality of life, and the potential benefits outweigh potential side effects of opioid therapy. Long-acting opioids should only be used in the setting of disabling pain, causing severe impairment to quality of life. ⁴˒⁸

Opioids are a broad class of medications with structural resemblance to the natural plant alkaloids found in opium.⁴˒⁸ Opioids are recognized as the most effective and widely used drugs in treating severe pain, but they have also been among the most controversial analgesics, mainly due to their potential for addiction, tolerance, and side effects. Although opioids have indications for acute and chronic pain treatment, the Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines recommends that only if the expected benefits for both pain and function outweigh the risks, healthcare professionals should consider opioids at the lowest effective dose and for the shortest expected duration to treat the pain. ⁴˒⁸

Most of the clinically relevant opioids act primarily at the mu receptors and thus are considered mu agonists, but they may also act on the kappa, delta, and sigma receptors as well. Depending on which receptor is activated, different physiologic effects occur. Side effects of opioids include ⁴˒⁸:

- Bradycardia

- Constipation

- Cough suppression

- Dysphoria/euphoria

- Hypotension

- Miosis

- Nausea and vomiting

- Opioid-induced hyperalgesia

- Physical dependence

- Pruritus

- Respiratory depression

- Tachycardia

- Urticaria

- Sedation

- Skeletal muscle rigidity

- Tolerance

Treatments will likely differ between individuals, but treatment is typically done in a stepwise fashion to reduce the duration and dosage of opioid analgesics. However, there is no singular approach appropriate for the treatment of pain in everyone. ¹˒¹⁷

The list of nonpharmacological therapies for chronic pain is extensive. Nonpharmacological options include acupuncture, aerobic exercise, chiropractic, cognitive behavioral therapy, group counseling, heat and cold therapy, physical therapy, relaxation therapy, and ultrasound stimulation. ¹³˒¹⁷ In addition, epidural steroid injections, nerve blocks, trigger point injections, and intrathecal pain pumps are some of the procedures and techniques commonly used to reduce symptoms of chronic pain. ¹³˒¹⁷ There is limited evidence of interventional approaches to pain management. For refractory pain, implantable intrathecal delivery systems are an option for people who have exhausted all other options.

Pain is a symptom, not a diagnosis. Persistent and under-treated painful conditions can lead to chronic pain. ¹² Thus, chronic pain is often a symptom of one or multiple diagnoses, but over time, the chronic pain itself can become a diagnosis. As such, it is critical to treat pain before chronic pain develops. To effectively treat pain, it is essential for the healthcare professional to determine what underlying disease processes or injuries are the cause of it. For instance, if an individual suffers from chronic knee pain, any potential contributing diagnosis such as osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis must be taken into consideration, and based on the diagnosis, an effective treatment regimen should be implemented.

Chronic pain increases the morbidity and mortality rate, and increases the rate of chronic disease, obesity, psychiatric illness, and suicide. The long-term prognosis for people with chronic pain demonstrates reduced function and quality of life. Improved outcomes are possible in people with chronic pain with effective pain management, and concomitant treatment of comorbid psychiatric illness.

Chronic pain is a significant public health concern with considerable morbidity and mortality. ¹⁴ Because of this, chronic pain should be managed by an interprofessional team, using a multimodal approach. Without proper pain management, an individual’s quality of life can be severely reduced.

Chronic pain correlates with several severe complications, including severe depression, suicide ideation, and suicide attempt. A team approach is an ideal way to limit the effects of chronic pain and its complications. Interprofessional team considerations area as follows ¹³:

- The individual should be evaluated by a healthcare professional to evaluate and treat any acute pain to prevent the pain from progressing to chronic pain.

- Conservative pain management should begin when symptoms are mild or moderate. Initial treatment considerations include cognitive-behavioral therapy, nonopioid pharmacological management, and physical therapy.

- A an expert knowledgeable in the medications frequently used to treat chronic pain should evaluate the medication regimen and include medication reconciliation to prevent drug interactions.

- The person experiencing pain should follow up with a healthcare professional to assess for pain improvement and adjust treatment regimens, as necessary.

- A mental health expert should address any comorbid psychiatric disorders that the individual may be experiencing.

- If symptoms worsen on follow up or if there is a concerning escalation of pharmacological requirements, including opioid use, a referral to a pain medicine specialist should be considered.

- If the individual experiencing pain has exhausted various pharmacological and nonpharmacological treatment options, interventional procedures should be considered.

- If the individual expresses concern for suicidal ideation or plan at any time, an emergent psychiatric evaluation must be conducted by a mental health expert.

- An individual who develops opioid dependence because of pharmacological therapy should be offered treatment through referral for addiction treatment. The individual should also be put on a medication weaning schedule, and medications to treat opioid dependence should be considered.

- As recommended by the Center for Disease Control, people are taking high-dose opioid medications or who have risk factors for opioid overdose, such as obesity, sleep apnea, concurrent benzodiazepine use, or others, should receive naloxone at home for the emergent treatment of an unintentional overdose.

Prevention is critical in the treatment of chronic pain, and chronic pain is best managed with an interprofessional team. A multimodal treatment approach is optimal to obtain better pain control and outcomes as well as to minimize the need for high-risk treatments such as opioids. When medication is required to control pain, the initial medication should be a nonopioid and the dose should be increased gradually, in a stepwise approach. If nonopioid medications are not effective in controlling pain, opioid medications may be considered, in addition to other modalities such as cognitive behavior therapy and physical therapy to help alleviate pain. The healthcare professional should also assess for comorbid psychiatric disorders and make the appropriate referral to a mental health expert when necessary.

Appropriately treating acute and subacute pain reduces the risk of it becoming chronic pain, which can negatively impact one’s quality of life. When chronic pain does occur, having the right treatment regimen can help improve symptoms and reduce morbidity and mortality.

1. Chelly, J. (2017). Faculty opinions recommendation of Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature.

2. Darnall, B. D. (2019). Pain-specific psychological factors. Psychological treatment for patients with chronic pain, 63-75.

3. Dirk, K., Rachor, G. S., & Knopp-Sihota, J. A. (2019). Pain assessment for nursing home residents. Nursing Research, 68(4), 324-328.

4. Hallvik, S. E., El Ibrahimi, S., Johnston, K., Geddes, J., Leichtling, G., Korthuis, P. T., & Hartung, D. M. (2021). Patient outcomes following opioid dose reduction among patients with chronic opioid therapy. Pain, Publish Ahead of Print.

5. Hutson, M., & Ward, A. (2015). Oxford textbook of musculoskeletal medicine. Oxford University Press.

6. Khan, S., Andrews, K. L., & Chin-Dusting, J. P. (2019). Cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors and cardiovascular risk: Are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs anti-inflammatory? International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(17), 4262.

7. Long, S. S. (2016). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Risks outweigh benefits. The Journal of Pediatrics, 175, 1-4.

8. Lubrano, M., Wanderer, J. P., & Ehrenfeld, J. M. (2015). Long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain. Annals of Internal Medicine, 163(2), 147.

9. Moayedi, M., & Davis, K. D. (2018). Neural mechanisms underlying pain. Oxford Scholarship Online

10. Pope, J. E., & Deer, T. R. (2019). Opioids for chronic non-cancer pain. Deer’s Treatment of Pain, 231-232.

11. Raja, S. (2010). 113 opioids for the treatment of chronic neuropathic pain: The evidence. European Journal of Pain Supplements, 4(S1), 34-34.

12. Rajasekar, S., & S Thotta, R. (2019). Assessment of quality of life in patients with chronic cancer pain using brief pain inventory.

13. Slaughter, T. (2018). Faculty opinions recommendation of effect of opioid vs Nonopioid medications on pain-related function in patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain: The SPACE randomized clinical trial. Faculty Opinions – Post-Publication Peer Review of the Biomedical Literature

14. Sleep, pain, and quality of life in chronic pain patients. (2020). Case Medical Research.

15. Sullivan, M. D. (2016). Why does depression promote long-term opioid use? Pain, 157(11), 2395-2396.

16. Van Den Noortgate, N., & Sampson, E. (2017). Pain assessment and management in cognitively intact and impaired patients. Oxford Textbook of Geriatric Medicine, 1203-1208.

17. Yvonne Buowari, D. (2021). Pain management in older persons. Update in Geriatrics.

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.