Contact Hours: 3

This online independent study activity is credited for 3 contact hours at completion.

Course Purpose

To provide healthcare providers with an overview of human trafficking in both the global and communal perspective and provide descriptors and behaviors of victims who may present to the healthcare setting.

Overview

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) brings human trafficking to the forefront of conversation on an international level. Prevention through education is paramount going forward in efforts to curb the growth of this $150 billion industry. Healthcare providers are on the frontline of these efforts as the first point of contact for most victims. Being able to identify the trafficking victim and provide resources is key to the victim becoming a survivor of human trafficking.

Objectives

By the end of this learning activity, the learner will be able to:

Define the various forms of human trafficking in the global and community setting

Describe indicators of potential trafficking and appropriate resources available

Identify actions the healthcare provider can take to assist the trafficking victim

Describe current legislatures that assist and protect trafficking victims

Policy Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of FastCEForLess.com. If you want to review our policy, click here.

Disclosures

Fast CE For Less, Inc. and its authors have no disclosures. There is no commercial support.

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.

| Coercion | Threats of serious harm to or physical restraint against any person; any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause a person to believe that failure to perform an act would result in serious harm to or physical restraint against any person; or the abuse or threatened abuse of the legal process. |

| Commercial Sex Act | Any sex act on account of which anything of value is given to or received by any person. |

| Debt Bondage | The status or condition of a debtor arising from a pledge by the debtor of his or her personal services or of those of a person under his or her control as a security for debt, if the value of those services as reasonably assessed is not applied toward the liquidation of the debt or the length and nature of those services are not respectively limited and defined. |

| Involuntary Servitude | Any scheme, plan, or pattern intended to cause a person to believe that, if the person did not enter or continue in such condition, that person or another person would suffer serious harm or physical restraint. |

| Labor Trafficking | The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for labor or services, using force, fraud, or coercion for the purposes of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery. |

| Revictimization | A situation in which the same person suffers from more than one criminal incident over a period. |

| Secondary Victimization | Victimization that occurs not as a direct result of the criminal act but through the response of institutions and individuals to the victim. |

| Sex Trafficking | The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, obtaining, patronizing, or soliciting of a person for the purposes of a commercial sex act, in which the commercial sex act is induced by force, fraud, or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained 18 years of age. |

| Smuggling | Differs from trafficking because it involves the illegal crossing of borders and is usually consensual. The relationship between the smuggler and the person being trafficked usually ends upon arrival to the destination country. Debt related to smuggling can lead to trafficking to pay back the smuggler. |

| Trafficking in Persons (TIP) | Also known as “modern-day slavery” is a crime in all 50 states under federal and international laws and does not require the physical transport of a person. It often occurs in local communities and schools, and near popular sporting venues. |

| Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) | An anti-trafficking federal law established in 2000 under President Clinton’s administration, “human trafficking” is defined as the exploitation of a person or persons for sex or labor using “force, fraud, or coercion.” |

Globally, human trafficking is a $150 billion industry. In fact, the International Labour Organization (ILO); an organization that brings together governments, employers and workers to set labor standards and develop policies that promote decent work for all women and men, estimated in 2016 that 40.3 million people were victimized worldwide through modern-day slavery, which amounts to 5.4 victims per every thousand people in the world. Of the 40.3 million victims in 2016, 29 million were women and girls (72% of total amount). Almost 5 million people in 2016 were victims of forced sexual exploitation globally, with children making up more than 20% of that number. According to new 2016 global estimates, 25 million persons have been subjected to forced labor worldwide, and 15.4 million in forced marriages. This data was collected by the ILO and the Walk Free Foundation (WFF); the world’s largest community dedicated to ending human trafficking and modern slavery, in partnership with the International Organization for Migration (IOM); an organization that promotes humane and orderly migration. The common thread that binds them together is the loss of freedom. Exact numbers of trafficking victims are unknown.²

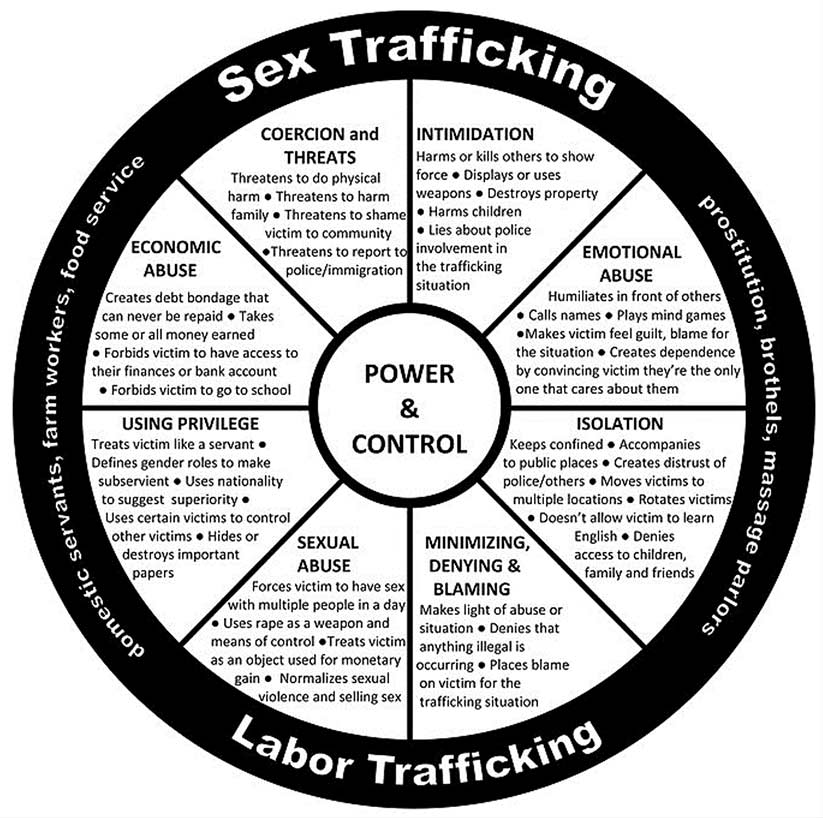

In the United States, human trafficking is a public health concern that transcends all races, socio-economic classes, demographics, and genders. Human traffickers are motivated by greed, driven by quota, devoid of respect for human rights, prey upon the vulnerable, and damage the psychological and physical well-being of their victims. Traffickers do not discriminate based on gender, race, social demographic, immigration status, or economic status. No exact mold fits a victim. Anyone is at risk, but certain populations have a higher vulnerability risk. Victims of sexual abuse are at increased risk for mental health issues, substance abuse, assault, domestic violence, and interpersonal or intimate partner violence. ¹¹ A trafficker preys upon this vulnerability and uses it to their advantage. Traffickers take the opportunity to exert power and control over a victim. Power and control manifestation take many forms of abuse on the part of the trafficker.

The Human Trafficking Power and Control Wheel finds its basis in the power and control wheel for domestic violence. The wheel for human trafficking depicts the different types of abuse inflicted on trafficking victims at the hands of traffickers. Power and control, the wheel center, represent the primary weapon a trafficker uses to the manipulate a victim and keep them bound to the trafficker.⁴²˒⁴³˒⁴⁴ Other tools in the arsenal to demoralize and dehumanize a victim involve behaviors such as:

This wheel was adapted from the Domestic Abuse Intervention

Project’s Duluth Model Power and Control Wheel, available at www.theduluthmodel.org

| Coercion and Threats | Threats of or actual physical abuse is another manipulation tool used to exert power and control over the victim. It may involve shoving, punching, hitting, kicking, and strangulation injuries. Torture can take the form of cigarette burns or branding or withholding basic needs such as food, water, and clothing. Threats to harm a child bind the victim to the trafficker for fear of no food or shelter or the actual threat of physical harm to the child. They may threaten to contact the Department of Children and Families or law enforcement. Traffickers may use drugs as a form of control over the victim. Either the introduction of drugs to the victim, or the threat to withhold drugs from a victim that is already struggling with addiction issues. These addiction issues may have led the person trafficked to the initial point of contact with the trafficker or be a result of trying to cope with the trafficking situation. |

| Economic Abuse | Debt bondage is employed as a tool to manipulate and control. The victim may get charged enormous interest rates that they can never repay. They are restricted from leaving their situation because they have no access to money, are allowed only a small allowance, or have any earnings confiscated. |

| Emotional Abuse | Emotional and psychological abuse can be particularly devastating to a victim. The trafficker humiliates the victim in front of others, calls them names, blames the victim for the situation, and convinces them that they would be all alone if the trafficker did not love and take care of them. The exploiter tells the person under their control repeatedly how worthless they are and that they are too weak to survive outside the existence the trafficker has created for them. They may threaten to expose or shame the victim by releasing sex tapes, nude photos, drug addiction, or participation in violence or sex acts against other victims. |

| Intimidation | Intimidation is another tactic used by the trafficker and involves physical violence inflicted upon children, pets, or other victims. It may include threats with a weapon or actual weapon use, destruction of property, and misleading information regarding police. |

| Isolation | A trafficker may keep a victim isolated by confinement, frequently move so the victim cannot become familiar with their surroundings or keep them cut-off from others by a language barrier. A victim may be isolated from family and friends or be accompanied by the trafficker while in a public place. The trafficker may not allow the victim access to routine, preventative medical care. Thus, medical problems may be exacerbated, and overall health compromised. |

| Minimizing, Denying, and Blaming | A trafficker often blames the victim and denies there is anything wrong with the situation, minimizes their involvement in the abuse or exploitation, and lets the victim think the victim is the reason for their current circumstance. |

| Sexual Abuse | Sexual assault may be useful to the trafficker as a means of power and control. The victim is treated as a sex object, only as good as the money he or she brings in. They may be forced to submit to sex with multiple partners daily or risk the wrath of the trafficker. Forced abortions, threats to end a pregnancy or violence during pregnancy are control tactics. Unwanted pregnancies, either through forced sexual assault or consensual sex, are a way to control a victim. |

| Using Citizenship or Residency Privilege | The trafficker may use privilege or superiority as a means of control. The trafficker may hide or threaten to destroy immigration papers such as work visas, passports, or other forms of identification. A victim might be used as a servant or as a pawn to entice others into trafficking. The trafficker or pimp may threaten the family, threaten to report to immigration. |

Each year, thousands of individuals fall victim to national and international trafficking. The 2016 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons revealed profile characteristics of the trafficker in relationship to that of the person who is trafficked. Traffickers tend to speak the same language as the victim, originate from the same geographical area, and share the same ethnic background. These commonalities foster a level of trust between the trafficker and the victim, allowing the trafficker to exploit the relationship for financial benefit. Traffickers rarely travel abroad to recruit, instead focusing on domestic recruitment. Countries most vulnerable to trafficking are those with high levels of organized crime and those ravaged by conflicts The Global Report on Trafficking in Persons reports 79% of classified trafficked individuals globally are women and children. It also found a clear link between migration and human trafficking, further reporting that the movement of migrants and refugees is the most substantial reported migration since World War II, with an estimated 244 million international migrants worldwide. Forced migration because of refugees fleeing war-torn areas makes the women, children, and boys especially vulnerable to exploitation by traffickers. There has also been a change in the victim profile over the past decade. The number of male victims is increasing. The movement of Syrians escaping the war is one such example. Children face exploitation as “child soldiers.” ¹⁴ Armed guards abduct individuals on migratory routes and exploit them as slaves for forced labor or sexual exploitation.

No country is immune from trafficking in persons. Sub-Saharan African and East Asian victims are trafficked to numerous global destinations. Affluent areas such as Western and Southern Europe, North America, and the Middle East have victims from all parts of the world. In Southeast Asia, forced marriages are on the rise. Central America, the Caribbean, and South America frequently report cases of girls becoming victims of sexual exploitation. Trafficking in fishing villages for forced labor is a problem in parts of the world such as Ghana and Taiwan. Overall, numbers of forced labor victims have increased, with 63% being men. Another alarming issue is that female participation was on the rise. Young girls are recruited and controlled by older women, and more couples are actively involved in trafficking. Posing as “stable couples” ¹⁴allows traffickers to seem more genuine and trustworthy while they actively recruit and exploit victims as a team. Victims can also become active participants in recruitment to reduce their debt bondage and end their own sexual exploitation. Still, others willingly participate in the abuse. If a person being trafficked is engaged in criminal activity, they are less likely to cooperate with police, thus allowing the trafficker even more control.

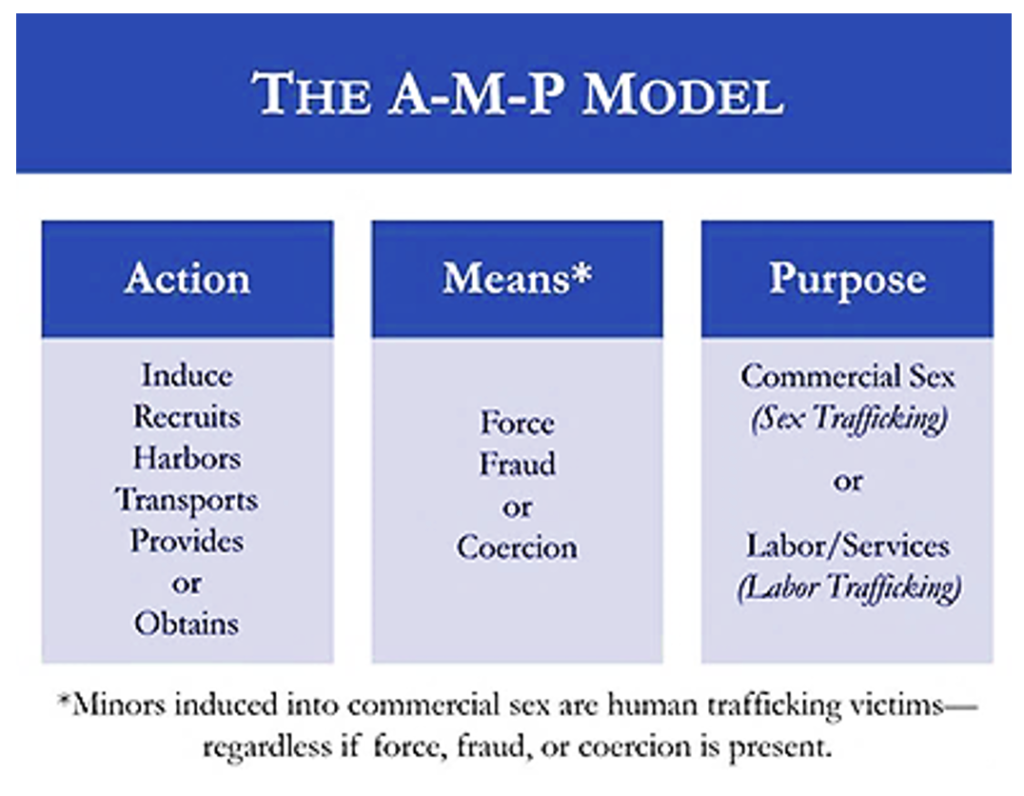

Human trafficking involves three essential elements: action, means, and purpose. According to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) and the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), the Action-Means-Purpose, or A-M-P Model helps determine whether force, fraud, or coercion was present, indicating the encounter was not consensual. In the A-M-P Model, human trafficking occurs when a perpetrator, often referred to as a trafficker, takes an action and then employs the means of force, fraud or coercion for the purpose of compelling the victim to provide commercial sex acts or labor or services. ⁴ Physical confinement is rare. Often, “invisible chains” are used to maintain power and control, such as what occurs in intimate partner violence. Fraud may include false claims of a job, marriage, promises of a better life, or a family. Coercion also involves threats, debt, or bondage that help foster a climate of fear and intimidation and may consist of abuse of the legal process.

The SOAR Campaign (Supplemental Security Income/ Social Security Disability Insurance, Outreach, Access and Recovery); training for case managers to assist people who have a mental illness, medical impairment, or have a substance abuse disorder and are at risk for homelessness, provided insight into trafficking in persons (TIPs) based on the latest amendments to the TVPA. For example, force may involve beatings, torture, rape, or imprisonment and can be psychological or physical. The SOAR Campaign further delineates at-risk, vulnerable individuals as those lacking a stable support structure or home life such as a runaway, foster child, or child in the juvenile justice system, a homeless youth, unaccompanied minor, persons displaced due to a natural disaster, and individuals that possess a language or cultural barrier. Increased risk also involves those with substance abuse problems, undocumented or migrant workers, and the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning LGBTQ population.

A critical distinction among the LGBTQ population was revealed by the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals had higher adverse childhood experiences (ACE) scores than their heterosexual counterparts. In this 2016 study, Austin, Herrick, and Proescholdbell concluded that the higher prevalence of ACES among LGB individuals might account for some of the increased risks for poor adult health outcomes, poor choices, and heightened risk of being trafficked. ¹ For instance, a transgender person may require hormone therapy that may be expensive, which puts them at risk for “survival sex” to gain money for hormone therapy. This vulnerable position of needing money to purchase black-market hormones at an inflated price with exorbitant interest rates can increase the chances of the transgender person being lured into trafficking. Fifty-five percent of transgender individuals who had resorted to “survival sex” ¹ in the past year were transgender women. Approximately 19% of them had participated in some form of “survival sex” for money, food, sleeping quarters, or other goods or services. In 2015, the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) conducted a survey, the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. The survey found that 10.8% of the overall respondents reported having participated in sex work and an additional 2.3% indicated that they had traded sex for rent or a place to stay, which poses an increased risk for sexual assault and intimate partner violence.

Similarly, transgender youths may have additional vulnerabilities that heighten their risk of being trafficked, such as depression, lack of financial or emotional support from family, homelessness, being victims of intimate partner violence, addiction, and history of sexual abuse as a child. It was reported in 2015 that transgender individuals with HIV also are vulnerable to being trafficked as they struggle to have their basic needs of food and shelter met. Minorities, those with disabilities, and those on Native American reservations can also be at a higher risk of being trafficked.

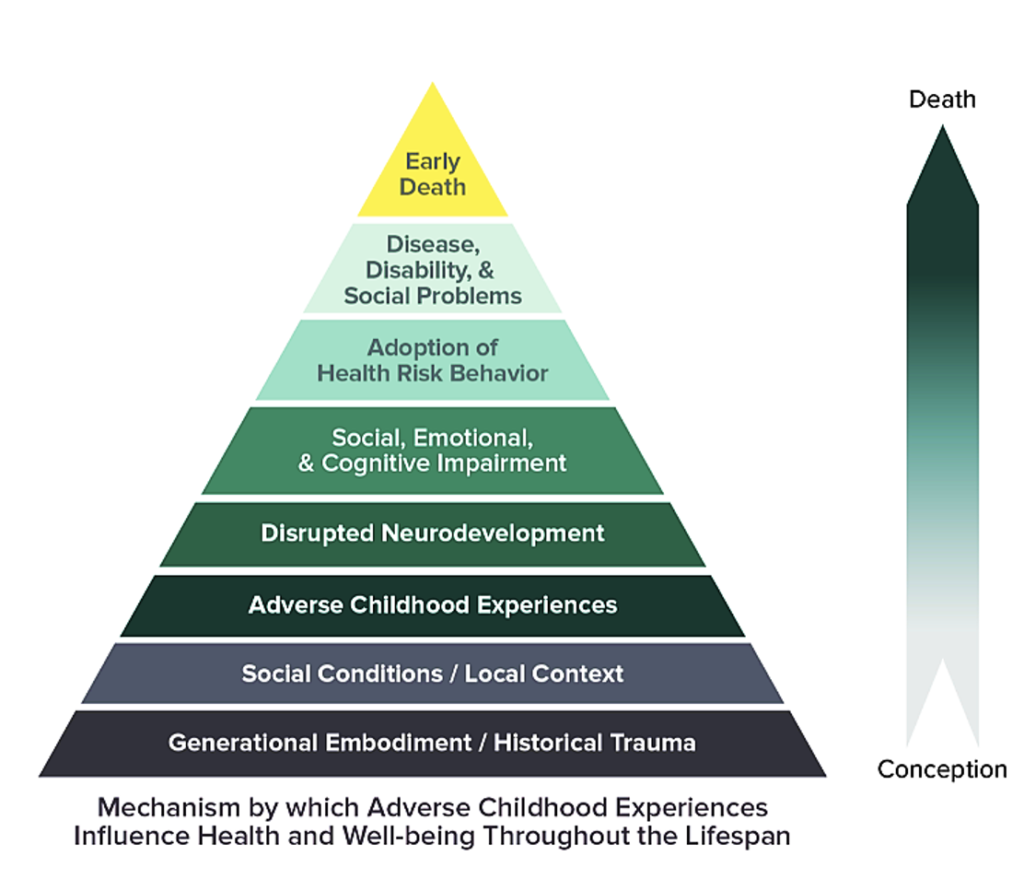

Human trafficking may be attributed to a multitude of factors that make a person susceptible to a trafficking situation, and one such contributing factor is related to adverse childhood experiences.

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) can increase the likelihood of risk-taking behavior that could predispose a person to a trafficking situation. A better understanding of how a high ACE score can increase the risk of a person becoming a victim of trafficking is best explored through research. The CDC-Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study is one of the largest investigations of childhood abuse and neglect and household challenges and later-life health and well-being.

The original ACE Study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente from 1995 to 1997. Over 17,000 health members from Southern California who received physical exams completed confidential surveys regarding their childhood experiences and current health status and behaviors. The ACE questionnaire asked difficult questions regarding the first 18 years of life. Questions are related to physical, emotional, and sexual abuse and the frequency of such occurrences. The suicide of a family member, drug addiction, and mental health issues played roles in the calculation of the score. ACE scores ranged from zero to 10, with zero representing no exposure.

The study uncovered how adverse childhood experiences are strongly related to development of risk factors for disease and well-being throughout life. It also found that ACEs are common across all populations, however some populations are more vulnerable to experiencing ACEs because of the social and economic conditions in which they live. Almost 66% of study participants reported at least one adverse childhood experience and more than 20% reported three or more adverse childhood experience.¹⁴ The ACE Pyramid conceptualizes the framework for the ACE study as it relates to individual health and well-being across the lifespan, from conception to death.

According to the adverse childhood experiences Pyramid, neurodevelopment is disrupted or stunted following an adverse childhood experience. Social, emotional, and cognitive impairments result, which progress to high-risk behaviors that negatively impact overall health. Disease, disability, and social problems ensue, cascading to an early death. Therefore, there is a correlation between a higher ACE score and an increased risk of poor physical and mental health due to poor choices, risky behaviors, and social issues.

A study conducted by Florida between 2009 and 2015 found trafficking abuse reports to be highest among children with an adverse childhood experience score of six or greater. Children with a sexual abuse history in connection with a higher ACE score had an increased chance of exploitation by traffickers.⁵

The US Department of Education published a fact sheet for schools entitled “Human Trafficking of Children in the United States” which discusses the vulnerability of school-age children as it relates to human trafficking. Examples of identified child trafficking cases involved:

| Agricultural work | Au pairs or nannies |

| Commercial sex | Drug sales and cultivation |

| Forced begging | Hair and nail salons |

| Magazine crews | Pornography |

| Restaurant work | Stripping |

Traffickers may target children through after-school programs, at shopping malls and bus depots, through social media websites, telephone chat-lines, in clubs, or through friends or acquaintances who recruit students on school campuses. Signs of child trafficking include⁵:

- An inability to attend school on a regular basis and/or having unexplained absences

- A child’s lack of control over his or her schedule and/or identification or travel documents

- IA child who is hungry, malnourished, deprived of sleep, or inappropriately dressed (based on weather conditions or surroundings)

- Making references to frequent travel to other cities

- Frequently running away from home

- Exhibiting bruises or other signs of physical trauma, withdrawn behavior, depression, anxiety, or fear

- Signs of drug addiction

- Having a rehearsed response to questions

- Demonstrating a sudden change in clothing, personal hygiene, relationships, or material possessions

- Acting uncharacteristically promiscuous and/or making references to sexual situations or terminology that are beyond age-specific norms

- Having a “boyfriend” or “girlfriend” who is noticeably older

- Attempting to conceal recent scars

- Signs that may indicate child labor trafficking include:

- Expressing need to pay off a debt

- Expressing concern for family members’ safety if he or she shares too much information

- Working long hours and receives little or no pay

Educational campaigns, such as the “Blue Campaign” created by the US Department of Homeland Security, offer much-needed insight into the identification and treatment of victims of human trafficking. The Blue Campaign offers sex trafficking awareness training and videos to provide education on the signs of trafficking, since it often occurs in familiar places such as schools, coffee shops, malls, sporting venues and other hangouts.

Myths or misperceptions often lead to missed opportunities to identify victims. It is essential for healthcare providers and first point-of-contact personnel to be educated on these potential myths. Trafficking in persons is not just a crime that occurs in a faraway place or one that only involves migrants or foreign nationals. Exploitation happens in every part of the world – in the suburbs, big cities, and hometowns. Victims can be coerced to take part in crimes and get arrested. They may present to the emergency department for medical clearance. Screening of these individuals is vital to identify victims, recognize the red flags of trafficking, and take appropriate action. Thinking this person is “just a criminal or “just a prostitute” is a bias that inhibits healthcare providers from reading verbal and nonverbal cues and recognizing a victim. A victim may fall into a revictimization situation if returned to an exploitative environment. If an individual is free to come and go, then they may not be recognized as a person being trafficked. A victim’s bondage to the trafficker is often psychological in nature and is not physical chains or cuffs. Fear paralyzes the victim, acting as a shackle that emotionally confines them to the trafficking situation. Mental weapons used by the trafficker to exercise power and control over a victim may include threats of harm to family members, deportation or return to a traumatizing situation, physical violence. Debt bondage, withholding of pay, and maintaining possession of all forms of identifying documents may further cause invisible bondage to the trafficker. Victims may use a school bus, a public bus, a taxi, or a train. Control over the person being trafficked lasts far beyond a physical wall, chain, or border. Much like intimate partner violence, victims usually do not self-identify, self-report, or recognize the fact that they are being manipulated, controlled, stigmatized, or dehumanized.

Traffickers may only seek out healthcare for their victims when they become seriously ill because it poses a risk for discovery of their activities. ²⁴ A multitude of factors should lead a healthcare provider to seek out medical services for a person who is a suspected victim of human trafficking such as:

- Emergent medical conditions such as profuse bleeding or pain caused by a beating or forced abortion, injury on a job site, or complications during pregnancy such as an ectopic pregnancy

- Gynecological services for sexually transmitted infections caused by debris in the vagina from packing during menstruation or forced sex without condom use

- Addiction issues such as severe overdose or withdrawal signs and symptoms

- Dental emergencies or plastic surgery consultations or complications

- Prenatal care or lack thereof

- Health-related mental problems such as depression, suicide attempt, anxiety disorder

- A patient on a psychiatric hold or court-mandated order

- Severe wound infections with signs of septicemia may force introduction into the healthcare system

Traffickers will seek out the quickest opportunities for care, and lengthy emergency department waits may lead to their decision to leave with the victim before receiving medical treatment. They may also “hospital shop” for quicker wait times from door to the provider. An accompanying “family member” that is impatient, aggressive, and upset over lengthy delays in overcrowded emergency rooms or clinics may, in fact, be a trafficker. Another indicator is the “spouse” or “boyfriend” that insists on a high-risk patient, such as one with a possible ectopic pregnancy or appendicitis, leaving without being seen, against medical advice, or eloping before care is completed.

Remember, a victim comes from all walks of life and may be perceived as having a stable home in a suburban community. No victim will look the same or act the same; their individual, unique responses to their traumatic event will follow no specific protocol. As healthcare providers, we must be diligent in our efforts to identify these silent victims, forced into a situation of no fault of their own, made to carry out acts that reap emotional and social ramifications for years to come.

Labor and sex trafficking carry inherent health risks and need exploration. Research studies in South Africa and West Bengal, India regarding the effects of sex trafficking and HIV risk determined that women and girls who experienced forced sexual encounters through being trafficked were 50% more likely to acquire HIV. One reason suggested that immature cervical epitheliums or cervical ectopy might lead to breaks in the vaginal mucosal and subsequent inflammation which increases the chance for HIV to spread during repeated sexual assaults in younger victims.³⁸˒²¹ Vulnerability and inexperience may also lead to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections due to inadequate condom use and repeated exposure to older adult males throughout the trafficking lifespan.

When treating these potential victims, screening for injury and sexually transmitted infections such as HIV/AIDS, herpes, syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, and hepatitis needs consideration. If a recent forced sexual encounter occurred, emergency contraception and sexually transmitted infection prophylaxis should be considered, following institutional guidelines. Sexual assault kits may need to be obtained. The healthcare provider should follow sexual assault collection of evidence protocols in their local area and per institutional policy. Pain from daily forced sexual encounters and trauma may be an issue. Problems with urinary tract issues may warrant a urinalysis or culture. A urine sample that is not a clean catch, often referred to as “dirty urine,” may be obtained to test for sexually transmitted infections. A pregnancy test may also be useful. Toxicology studies may be needed, and alcohol levels and withdrawal issues should be addressed.

Complications surrounding forced tampon use or “packing of the vagina” by traffickers to facilitate sexual encounters (unnoticeable to customers) while victims are menstruating may be of concern. Foreign debris may be present in the vagina on pelvic examination, and cervical cultures are a possibility if any discharge is present. That “lost tampon” patient may be a victim of trafficking and require a more in-depth assessment, asking open-ended, neutral questions to spot red flags.

Labor trafficking victims may experience severe dehydration or malnutrition due to being forced to work long hours in construction, on farms, at factories, or in “sweatshops.” Heat exhaustion or hypothermia may present in these trafficking victims. According to the 2016 Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, Southeast Asia is emerging as a destination for short, medium, and long-distance trafficking. Increasing in frequency, these victims are made to endure long ocean voyages as they are smuggled into the United States and other countries on cargo ships. These overcrowded, unsanitary conditions have infectious disease ramifications.³⁹˒⁸ Communicable or infectious diseases such as silicosis, tuberculosis, HIV, and typhoid may be an issue. Scabies, lice, and bacterial and fungal skin infections may be a concern. Malaria, Chagas disease, cysticercosis, toxoplasmosis, toxocariasis, and trichomoniasis also may be risks. Asbestos concerns exist for miners who are victims of labor trafficking. ⁴¹ Migrant workers who are being trafficked in the fishing and seafood industry may suffer from exposure to Vibrio vulnificus and subsequent necrotizing fasciitis with septicemia if left untreated. Vibrio vulnificus, found in warm climates with shallow, coastal waters, can infect a person through lacerations or breaks in their skin. Labor trafficking victims may suffer from injuries related to poor ergonomics, such as back and neck injuries, vision problems, carpal tunnel syndrome, and headaches.

Healthcare providers, for a variety of reasons, may fail to stop, observe, and ask questions to identify a potential victim of human trafficking. Biases, fear of no available resources, lack of education regarding human trafficking red flags, lack of privacy, myths, the absence of protocols, stereotypes, time constraints, the victim declining to give a history and self-identify, or an inability to separate the person from the potential trafficker all may play a part in the inability to identify victims.

Language barriers and cultural misconceptions may lead to a missed opportunity to identify a potential victim.²² Inconsistencies in stories or medical history may become lost in translation, especially if a healthcare provider fails to obtain a certified interpreter who has no relationship to the person being exploited. A staff member versed in the same language or who shares the same culture as the victim may be able to spot these subtle clues and ease cultural shock and miscommunication, but it is not always feasible in a busy healthcare setting. Behaviors passed off as cultural may be a form of demographic profiling that creates an environment to miss red flags.

Also, a patient who presents with multiple visits for a pain complaint that has no organic cause, a “frequent flyer” as labeled by some, may be a victim of trafficking but stereotyped and overlooked. Those problematic patients that present with stress-related issues on multiple visits or those who return over and over with psychological holds for overdoses or suicidal ideations may be victims of trafficking. Each time, there is the risk that they will be released back into the trafficking situation and revictimization. Healthcare providers must be attuned to their own emotions and potential for bias.²⁷ Traffickers can pose as parents, grandparents, or spouses. As a healthcare provider, one must stop, observe, ask, and respond⁴ to suspected trafficking. It is imperative that if a suspected case of human trafficking or intimate partner violence arises that no family member or accompanying party be allowed to translate. Ensure a certified interpreter from the hospital/institution is obtained.

According to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center (NHTRC) and hotline, general signs of sex trafficking in persons may include but not be limited to the following with some modifications:

- Inconsistent history or a history that appears coaxed. It may be difficult to determine if a language barrier is present.

- Resistant to answer questions about the injury or incident.

- Avoids eye contact, is nervous, fearful of touch.

- No idea of address or general area where they live.

- No control over their finances and lacks decision-making capacity.

- Accompanied by a controlling companion or family member that refuses to let the patient speak for themselves or be alone for care or insists on being the translator.

- Exhibits bizarre, hostile behavior. Resistant to care and assistance. May have initially consented but changes mind after asked to undress for an exam.

- No identification or the companion has it in their possession.

- Under age 18 and involved in a commercial sex act.

- Tattoos or branding signs. Markings may say “daddy” “for sale,” imply ownership, or read as an advertisement for a product.

- Multiple sex partners.

- Inappropriate attire for the environmental conditions of the area.

- Attempt to reason away bruises or ligature marks by claiming a bruising or rare blood disorder.

- Silent, afraid to speak, cringes at the sound of a loud voice.

- Uses trafficking “lingo” such as “the life” or other words common in the commercial sex industry.

- Have addiction issues such as opioids.

- Admits to a forced sexual encounter or being forced into sex acts.

Common presenting complaints of victims of human trafficking are much like those of intimate partner violence but may vary depending on if a victim of labor versus sex trafficking. Labor traffickers prey on specific vulnerabilities to entice individuals to accept substandard working conditions. Workers in the agriculture industry, factories, and domestic servitude sectors are vulnerable to human trafficking due to their work visa and immigration status being controlled by one employer. This power over the individual and fear of deportation allows the trafficker to manipulate the worker, leading to victimization. Also, agricultural, and industrial workers who are forced to work long hours with substandard wages may be isolated, confined using armed guards, barbed wire or other fences, dogs, and locks. The seasonal nature of their work and movement from place to place heightens their vulnerability due to regularly being subjected to unfamiliar surroundings. Domestic workers are also isolated, forced to live on the premises, and may lack access to cell phones and other communication devices. Labor laws may not apply to subcontractors or independent contractors, thus increasing vulnerability risk. Language barriers also add to vulnerability because of not being able to communicate. A common theme occurs between trafficking victims and their traffickers; keep the victim isolated by proximity or language, keep them vulnerable due to immigration status, ensure they don’t have resources and owe debts, shelter them from the protection of labor laws, and increase the ability to control and manipulate them.

When healthcare workers encounter potential victims of trafficking, a detailed work history and social history will assist in identifying red flags. A better understanding of the most common areas where persons are targeted for exploitation will help healthcare providers assess a potential victim. Labor trafficking victims tend to be near factories, farms, fisheries, or businesses such as massage parlors, nail salons, restaurants, and areas with high immigrant populations. Construction workers, domestic workers, landscapers, nannies, elder adult caregivers, traveling sales crews, and those in retail have a heightened risk of being labor trafficked. Immigrants may lack the power of communication because of language barriers, which allows traffickers from a similar background to approach and take advantage of them.

Sex trafficking can be hotel or motel based, in residences functioning as brothels, and street based. Bars, commercial-front brothels, escort services, strip clubs, and truck stops can be places where sex trafficking occurs. Sex trafficking can happen at home with parents, intimate partners, or other family members as the perpetrators. Victims may not see themselves as victims and may refer to the trafficker as their “daddy” or “boyfriend.” ¹⁹

Stop, Observe, Ask, and Respond (SOAR) will guide healthcare providers in determining whether red flags indicate a potential case of human trafficking. Healthcare providers must determine if a crime occurred or if all three elements of trafficking in persons exist: force, fraud, and coercion. The healthcare provider’s role is to recognize a potential case of human trafficking, empower the person being exploited, educate the victim on resources and established support structures, and provide a framework for a trauma-informed, victim-centered approach to healthcare. Observing for verbal and nonverbal clues as well as asking open-ended questions in a private, non-judgmental way will assist healthcare providers to determine a potential case of human trafficking. Questions to ask regarding labor trafficking suspicions may include and not be limited to the list below.

- Are you being paid the wages that were part of the initial agreement?

- Can you change jobs if you want to?

- Would anything happen to you if you did quit your job?

- Can you come and go as you please, take bathroom breaks, eat when you want?

- Do you live with others? What are the home conditions and where do you sleep? Do you have a bed? Do you sleep on the floor? Is it too cold or too hot?

- Did you pay a fee to get your job? Do you owe a debt to your employer?

- Do you have access to your money, your identification?

- Has your employer ever threatened you?

- Did you have eye protection, a mask, a safety harness? Personal protective equipment such as gloves? Respirators?

- Does your employer provide your housing?

- Are you working in the job you were hired to do?

- Are you concerned about your safety? Your family or children’s safety?

- How many hours do you work a day? How many days per week?

- Have you moved around a lot? Do you know your address? Can you give me directions or a location of your house?

- Do you take care of others?

- Are there locks on the doors or bars on the windows? Can you leave freely?

Languages are essential to the understanding of different cultures, environments, enterprises, and socioeconomic groups. Human trafficking and smuggling have a dialect, unique to traffickers and victims. Exploration of trafficking vocabulary will help healthcare providers relate to and understand victims who have been trafficked. It is imperative in a victim-centered approach, much like a patient-centered approach, to communicate effectively with a potential victim or patient. The following are legal definitions and terms, or “lingo” used by traffickers and victims as they relate to human trafficking. Other terms may become recognizable as jargon unique to a trafficking situation.

| Bottom | A victim who is chosen by the pimp or trafficker to “handle” the other victims. They may train the new victim, post ads, control social media posts, inflict punishment if rules get broken, and book the “date.” This individual victim may feel tremendous shame and guilt because of her actions and treatment of other victims. The pimp may further control the “bottom” by threatening violence, increased quotas, or reporting her to the authorities. The “bottom” may be required to entice others into servitude by posing as a student, a concerned friend, a mother-figure. |

| Branding | A carving, tattoo, or mark on a victim that implies ownership by a pimp/gang/trafficker. The tattoo may say, “Daddy,” “Property of…,” or “For sale.” |

| Circuit | A series of places where prostitutes/victims get moved. Keeping them in unfamiliar surroundings increases their vulnerability and facilitates the trafficker’s control over the individual. |

| Daddy | The word a victim is required to call their pimp/trafficker. |

| Date | The time and location where the sex act is to take place. The buyer or “john” meet them at this pre-determined site. |

| Gorilla Pimp | A trafficker or pimp that resorts to violence to control a victim. |

| Quota | The amount of money expected from their trafficker/pimp each night. If quotas go unmet, the victim may be beaten, tortured, or made to work exorbitant hours until the expected amount has been delivered. |

| Romeo/Finesse Pimp | The trafficker that uses a false romance; a false promise of money, clothing, or other gifts; or false hope of marriage to lure victims. Often referred to as “boyfriend.” |

| The Life | Sex-trafficking victims refer to their situation as being in “the life.” |

Conducting a full assessment in this vulnerable population is of vital importance. An examination may prove difficult due to the emotional and psychological state of the victim. Human trafficking victims may appear to be uncooperative and give an inconsistent history. These reactions are manifestations of their trauma. Healthcare providers’ frustration or stereotyping may arise, leading to the desire to exit the room quickly, with a quick determination of probable diagnosis and treatment. As with any trauma patient, a high index of suspicion should be present for co-existing conditions and comorbidities.

A healthcare provider must conduct the assessment in private, and not allow anyone who accompanied the patient to be present. A chaperone may be present as well as a certified interpreter, if required, to facilitate a feeling of trust and establish rapport. A same sex healthcare provider should also conduct the physical exam/assessment if possible. During the exam, the patient may seem emotionally absent, hyperventilate, and not verbalize feelings of discomfort. The healthcare provider must be alert to nonverbal signs, frequently reassure the patient, and promote a relaxed, non-rushed atmosphere. They also should avoid interrogating the victim, and only ask direct, pertinent, open-ended, neutral questions. The healthcare provider should also maintain eye contact with the victim while being sensitive cultural considerations and avoid writing while the victim is speaking. They should also ensure the victim is completely undressed and, in a gown, so a complete trauma assessment can be initiated, which should specifically examine for the following:³⁰

- Bruising: multiple bruises in various stages of healing, hematomas, signs of acute or chronic head trauma or a headache, missing hair, or bald spots.

- Trouble hearing: damage to the auditory canal or eardrum, signs of trauma to the oropharynx such as lacerations or burns, blood in the mouth, ulcerations, tooth decay, broken teeth, gingival irritation, tongue abnormalities, signs of anemia or dehydration in the oral mucosa.

- Visual defects: sudden or of gradual onset, tattoos, or brands in the hairline or on the neck, signs of strangulation such as bruising.

- Signs of chest trauma: murmurs, cigarette burns, tattoos that imply ownership, bruising in various stages of healing, signs of stress-related cardiovascular issues such as arrhythmias or high blood pressure.

- Respiratory issues that would indicate inhalation injuries from chemical exposure, toxic fume exposure, asbestos exposure, or mold exposure.

- Signs of tuberculosis such as night sweats, coughing up blood, fever, weight loss.

- Signs of stress-related respiratory or gastrointestinal problems.

- Damage to lung tissue due to prolonged exposure to chemicals or pesticides, aspiration pneumonia or other inhalation injuries, meth lab exposure can produce burning to the eyes, nose, and mouth, chest pain, cough, lack of coordination, nausea, and dizziness.

- Hypothermia or hyperthermia from environmental exposure from working in damp, cool, poorly insulated factories or buildings, signs, and symptoms of mold exposure.

- Signs of gastrointestinal issues such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or abdomen pain, rectal pain, itching, trauma or bleeding, parasites in the feces or signs of abdominal trauma.

- Bruising to the back or scarring, tattoos that imply advertisement, ownership, or are sexually explicit in the pubic hair.

- Obstetrical and gynecological complaints such as sexually transmitted infections or recurrent sexually transmitted infections (STI) (a recurrent STI in a minor may be the only sign of sexual abuse), repeated unwanted or unplanned pregnancies or forced abortions, anogenital trauma, evidence of retained foreign bodies such as in the vagina from packing during menstruation, vaginal bleeding, discharge, rashes, itching, signs of injury or forced sex.

- Number of sexual partners, condom use, genitourinary symptoms present such as burning, frequency, odor, dark urine, or history of frequent urinary tract infections.

- Signs of bruising or lower back scarring from repeated beatings, musculoskeletal issues such as signs of repetitive trauma, work-related injuries or injuries such as back problems from wearing heels for hours walking the streets or neck and jaw problems from frequent, forced oral sex.

- Old or new fractures and any contractures, cigarette or scald burns, ligature marks/scars around ankles or wrists. Signs of scabies, infestations, impetigo, fungal infections.

- Signs of nutritional deficits such as Vitamin D deficiencies from lack of exposure to sunlight, anemia, mineral deficiencies, brittle or fine hair.

- Signs of anorexia, bulimia, loss of appetite, malnutrition, severe electrolyte abnormalities.

- Children may have growth and development abnormalities and dental cavities or misaligned poorly formed teeth.

- Neurological issues such as seizures, pseudo-seizures, numbness or tingling, migraines, inability to concentrate, vertigo, unexplained memory loss.

- Insomnia, nightmares, waking up frequently.

- Signs of opioid or other addiction.

- Signs of physical torture may be present on a dermatological evaluation such as abrasions over bony prominences, scratches, or linear abrasions from a wire, or “road rash” to extremities from being thrown from or drug by a vehicle. Ropes and cords can leave elongated, broad-type abrasions. Ropes may leave areas of bruising mixed with abrasions. Belts or cords may have loop marks or leave parallel lines of petechia with central sparing. Tramline bruising, two parallel lines of bruising, can result from being beaten with a heavy stick or baton. Cigarette burns tend to be circular with a 1 cm diameter and can fade in a few hours or a few days. Burns, in general, tend to take the shape of the object that inflicted the burn.

It is important to note that some cultures practice cupping therapy and may have bruising and scars from this practice. Correlate this finding with a detailed history as well as the presence of other red flags.

Mental health indicators of trafficking in persons may be missed or explained away as a panic attack. Again, the healthcare provider must stop and take an in-depth assessment while considering the flags. The healthcare provider should look for signs such as depression, suicidal ideations, self-mutilation injuries, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and feelings of shame or guilt. Shame may keep a victim bound to a trafficking situation. It is often used as a tool of control by a trafficker. Does the patient report nightmares, flashbacks, irrational fears, irritability, social isolation, suicidal ideations, or depression?

A trafficking victim may describe a situation as if they were an outsider looking in; a mind-body separation, creating a safe, alternate reality to cope with the atrocities they are facing and feelings of shame and guilt. They take a third-person, omniscient point of view in their storyline since this is the most trusted viewpoint. Sometimes patients exhibiting this behavior are categorized as impersonal or devoid of emotion, numb to their surroundings, or detached. This is their survival mechanism.

Addiction issues may be present and result in withdrawal. The addiction may be fueled by the trafficker for control or by the victim to cope with the physical or emotional pain surrounding the trafficking situation.

Has a cover story to avert suspicion, but details may vary or be inconsistent with a query. Law enforcement may refer to this as a “legend.”

Once a healthcare provider identifies a potential trafficked person, it is imperative to establish a private, quiet, safe place to assess the patient further, much like in cases of child or elder abuse. Building rapport and providing an opportunity for the victim to feel empowered is of utmost importance and builds trust. The healthcare provider should not start a dialogue until a safe, private, and secure place is established. During the discussion, the healthcare provider must inform the potential victim of trafficking that they are mandated by law to report certain disclosures.

In this era of mobile devices where a smartphone is always within easy grasp, ensure cell phones are off and not nearby. Cell phones can be another way the traffickers control the victim. The victim may have arrived alone but is always on her cell phone. The cell phone may be the trafficker’s way of “keeping tabs” or listening to everything going on in the room.

While maintaining eye contact during conversation, the healthcare provider should speak slowly and quietly, and avoid looking down at the potential victim. Instead, the healthcare provider should sit in a nearby chair where same-level eye contact is possible, unless it is contrary to the patient’s cultural norms. The healthcare provider must also ensure the environment is a place where the victim can establish a sense of power and control. This empowering zone of safety may allow the trafficking victim to open up and admit they are a victim, and more importantly, it may provide a venue for opportunity, resources, and the realization they are not alone and that help is available if they choose to accept it.

The healthcare provider must never assume that it is safe for the victim to speak; they must confirm that it is safe prior to having any discussions thorough verbal and nonverbal cues. Safety is critical for the victim, staff, and nearby patients. Trafficking protocols will guide the healthcare provider’s care and determine a preset location that is readily available for an interview or a few minutes alone with the patient. A bereavement room set up for family notification in the event of trauma or sudden death may be one such place.

Communicating with victims of human trafficking can be intimidating for health-care providers. To improve communication, the Department of Human Health Services created a resource called Messages for Communicating with Victims of Human Trafficking as part of their Rescue and Restore Campaign in 2016. These messages assist healthcare providers in building a rapport with the victim and promoting a trusting environment. Sample messages for communicating with a victim of human trafficking includes:³⁶

- We are here to help you, and our priority is your safety. We can keep you safe and protected.

- We can provide you with the medical care you need as well as find you a place to stay.

- Everyone has the right to live without being abused or hurt, and that includes you.

- You deserve a chance to live on your own and take care of yourself, be independent, and make your own choices. We can help you with that.

- We can get you help to protect your family and your children.

- You have rights and deserve to be treated according to those rights.

- You can trust me. I will do everything within my power to help you. Assistance is available for you under the law, and there are special visas to allow you to live safely in this country.

- No one should have to be afraid all the time. We can help.

- Help us, so this does not happen to anyone else.

- You can decide what is best for you but let me provide you with a number to call for help 24-hours a day. You do not even have to tell them your name if you do not want to. They are there to help you anytime day or night. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center hotline number is 1.888.3737.888.

During conversations with the identified trafficking victim, the healthcare provider should not make false promises; instead, offering what the can access and realistically provide.

The trafficker may be the accompanying family member or significant other that declines to leave the patient alone. Like intimate partner violence, the healthcare provider must create an opportunity to separate the victim from the trafficker. For instance, they can take the patient to the bathroom for a urine sample or to radiology for an x-ray and inform the suspected trafficker that they cannot go with the patient. Another way to get the victim alone is to notify the suspected trafficker that hospital policy requires you to interview and examine everyone alone. Before the healthcare provider separates the potential victim from the suspected trafficker or controlling individual, they must make sure that they or a dedicated, trained staff member has the time to conduct an interview/assessment at that moment.

Traffickers can be parents, boyfriends, husbands, women, men, friends, and those you would otherwise see as protectors. If privacy cannot be obtained to interview the suspected victim alone, do not confront the situation. The trafficker may cause the victim serious bodily injury after removing them from the facility if alerted to the fact that the healthcare provider is suspicious of the situation.

If a patient reveals they are a victim of human trafficking, the healthcare provider should ask the patient if it is alright to call the national human trafficking resource center hotline number. The healthcare provider should also provide the victim with the phone number and encourage them to call the hotline. It may be dangerous for the victim to keep the number on hand. The healthcare provider should ask if they can memorize it or give them a “shoe” or “key” card that can be hidden in their shoe or other discrete location.

The National Human Trafficking and Resource Center (NHTRC) hotline number is available around the clock and is confidential to the extent of the law. The NHTRC is a tip hotline, a place to find out about services and to ask for help. The hotline can translate and communicate with individuals in more than 200 languages. A caller does not need to disclose any personal information to the hotline; it can be anonymous.

When a victim of trafficking reveals themselves, it is imperative that the healthcare provider assess the level of danger or threat to the patient and staff. The healthcare provider must pay attention to the immediate area and follow preset protocols by the institution in notifying law enforcement and security personnel. The national human trafficking hotline resource center can also assist the healthcare provider in assessing the threat level, danger risk, and the contacting of law enforcement if the patient consents. When dealing with a trafficking victim, having an interprofessional approach with a trained social worker is best, as predetermined by the institution protocols. The healthcare provider must follow preset policies and procedures regarding abuse and neglect at their institution and according to local and state statute. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center is available to help healthcare providers in the event of a potential trafficking case when no protocols are available. Healthcare providers can gain information in social referrals such as anti-trafficking organizations, shelters, local social services agencies, legal services, and law enforcement numbers. Tip reporting is also available. The hotline provides training information and technical support on their website. The NHTRC can guide a healthcare provider in an assessment of a potential victim.

- Call: 1-888-373-7888 (24/7)

- Email: nhtrc@polarisproject.org

- Text “HELP” to 233733 (BEFREE)

Guidelines for the reporting of suspected cases of human trafficking for adults and children will vary depending on facility, location, state, and federal laws. Adults may not want to report the incident. Consideration should be given in the decision to alert law enforcement based on predetermined protocols and local or state laws coupled with patient wishes. Some states mandate reporting if serious bodily injury or a firearm is involved.

When the healthcare provider obtains permission from an adult victim of human trafficking to release any protected health information or personally identifiable health information to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center, it is essential to consider Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) concerns. HIPAA will permit the release of protected health information under certain circumstances such as suspected injury or abuse. For example, if the law mandates a disclosure as in the case of child abuse or neglect, elder abuse, or neglect, and in cases reportable to the medical examiner. Reporting is permissible under HIPAA regulations if the disclosure involves a crime in an emergency, any disclosures necessary to prevent harm if the victim consents to the disclosure, and any situation where local, state, or federal law requires reporting. The National Human Trafficking Resource Center may be contacted and provided general information for a consult if no protected, identifiable health information is released. If the victim is under the age of 18 and involved in a commercial sex act, then the healthcare provider should follow the child abuse reporting laws in their state and the child abuse policies in their institution.

Another resource for reporting cases and gaining information as it relates to the trafficking of minors is the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC). In 2016, The NCMEC estimated that one in six endangered runaways were likely victims of sex trafficking. Children as young as nine are thought to be targeted by sex traffickers, with the average age between 11 and 14. Labor trafficking ages vary. To report sexually exploited or abused minors, the healthcare provider should call the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children’s (NCMEC) hotline at 1-800-THE-LOST, 1-800-843-5678.

- In the case of an immediate emergency, they should call the local police department or emergency access number.

- Child protective services and local law enforcement will assist healthcare providers in local reporting requirements for minors involved in a possible abuse situation. Ages of sexual consent may vary from state to state, thus local agencies should be consulted.

Long-term psychological impacts must be taken into consideration when referrals for treatment of trafficking victims are enacted into a treatment plan. Multifarious conditions exist emotionally and physically, rendering approaches to future care a challenge for healthcare providers.

According to the findings of a study of male and female survivors of trafficking in England conducted between 2013 to 2014, healthcare, including physical, mental, and sexual healthcare, must be a fundamental component of post-trafficking care. Follow-up care coordinated with multiple disciplines is essential. Basic needs of clothing, food, safe shelter, and transportation must be discussed. Language barriers must be addressed, and the victim must be provided resources on free classes to learn the local language. Potential referrals include:

- Dietician consults in cases of severe malnutrition.

- Infectious disease consults for communicable diseases and sexually transmitted infections.

- Referral to obstetrics/gynecology for infertility concerns related to forced abortions, repeated trauma, or frequent miscarriages or medical problems such as prenatal concerns, addiction issues, torch infections, originating from lack of preventative care or poor access to care may need investigation. Hormone replacement therapy concerns must be met for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) victims.

- Surgical or dermatology referrals for removal of unwanted tattoos or brands or to treat burns and other injuries.

- Consultations with gastroenterologists for stress-related issues.

- Children often suffer developmental delays and need assistance with transitioning into a healthy life.

- Social stigma implications of forced homosexuality can play a role in future psychological care. Crisis intervention teams and case managers will have a role in successful integration practices.

- Perpetrators often use substance abuse to control victims, or victims use it as a form of escape from the abusive environment. Addiction and sobriety considerations will need implementing into daily routines. Community-based organizations, support groups, and faith-based programs may ease this transition period and lessen the impact of psychological stressors.

- Legal services referrals made for child custody issues, immigration assistance, protective/restraining orders, assistance with any offenses, and with the successful prosecution of the trafficking entity.

Documentation of physical findings and interventions is important and may assist the victim in prosecuting their trafficker later if health records get subpoenaed. The healthcare provider should follow established documentation guidelines and reporting requirements based on state and local statute or federal law. Photo documentation may prove vital. The healthcare provider should follow all protocols and policies specific to their institution regarding obtaining the required consents for taking and storing photographs. ³²

Cultural shock impacts and language barriers play a role in the recovery period and successful transition into society as a survivor and not a victim. Survivors of human trafficking can offer much-needed insight into the thoughts, feelings, and interactions with members of the healthcare team and guide care and training programs going forward with this vulnerable population.

In 2015, a study conducted in New York City’s Rikers Island jail suggested that survivor-based input was essential in addressing healthcare concerns and improving care for the trafficked victim. Themes originated from these victims regarding healthcare providers included feeling intimidated, judged, and stereotyped. They suggested providers and front-line personnel pay attention to their body language and nonverbal cues they are displaying as they walk into the treatment room, up to the front desk, or after disclosure. This interaction, if negative, can impact a victim feeling safe enough to be forthcoming with pertinent information. The victims emphasized an approach of communication that asked direct, normalized questions in a compassionate, nonjudgmental way that reinforced a feeling of safety and confidentiality

The United States Congress has passed several comprehensive bills to expose human trafficking crimes in domestic and international communities. This legislative process finds its basis in the 13th Amendment to the US Constitution which banned involuntary servitude and slavery in 1865. One such law, adopted in 2000, was the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which combats trafficking in persons (TIPs) using the “3 Ps” approach: Protection, Prosecution, and Prevention.⁶

- Protection:

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA) established several protective measures for trafficking victims located in the United States. Regardless of immigration status, foreigners who are trafficked are eligible for federally funded benefits, such as healthcare and immigration assistance. The T nonimmigrant status (T visa) is a temporary immigration benefit that enables certain victims of severe human trafficking to remain in the United States for up to 4 years if they have assisted law enforcement in the investigation or prosecution of human traffickers. Upon returning to their originating country, human trafficking victims are vulnerable to re-trafficking within two years of first being trafficked because of psychological, emotional, and economic conditions. Reintegration into society and functioning within societal norms can be traumatic for a victim who has already been traumatized from trafficking exploitation.

- Prosecution

Under the Trafficking Victims Protection Act, federal prosecutors were able to prosecute traffickers for their crimes against humanity. The existing statutes were broadened, and the new legislation mandated financial restitution to the victims they exploited through trafficking and offered stronger penalties for those convicted of trafficking crimes. Revisions of the TVPA and subsequent enactments further defined human trafficking as “severe forms of trafficking in persons” including both sex trafficking and labor trafficking.

- Prevention

The Trafficking Victims Protection Act strengthened prevention efforts on behalf of the United States government through the creation of the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. This agency was created within the US Department of State and has incentives to improve economic conditions around the world to deter trafficking in persons. Annual trafficking in persons (TIP) reporting is mandated and countries are rated on their efforts to reduce TIPs according to the US Department of State. ⁹

The US Department of State also assists in prosecuting human trafficking and smuggling cases. Diplomatic Security Service (DSS) agents and analysts often support foreign law enforcement agencies to combat the global epidemic of trafficking in persons. Domestically, the US Department of State has a working relationship with federal, local, state, and tribal leaders to investigate potential cases of “modern-day slavery” for sex or labor exploitation.

Also, the Trafficking Victims Protection Act required the creation of an Interagency Task Force to monitor and combat trafficking. Reauthorizations of the TVPA were enacted in 2003, 2005, 2008, and most recently in 2013. The Justice for Victims of Trafficking Act was adopted in 2015 and allowed for additional tools to address human trafficking. The initiatives directed the Attorney General to create a National Strategy to Combat Human Trafficking and ensure its ongoing maintenance. ¹²

Healthcare providers must know human trafficking protocols in their institutions and know the local resources available. Local resources such as Project Help, rape crisis centers, women’s shelters, homeless shelters, addiction centers, and churches can provide needed materials and support services for victims. Human trafficking protocols have vital elements such as indicators, red flags, ways to separate the potential victim from the trafficker, interview procedures, ways to maintain and ensure safety for the victim, staff, and potentially other victims and referral information. Mandatory reporting requirements that address local, state, and federal laws are also in a protocol. Referrals, including the NHTRC Hotline information must be accurate and easily understood by the victim and translated appropriately based on language needs.

As front-line participants in the battle to combat human trafficking, healthcare providers must be aware of the potential barriers to victim identification and able to effectively communicate with suspected trafficking victim. Human trafficking care must involve knowledge where the healthcare provider recognizes the scope of the impact on a victim’s lifespan and ensures to lessen any chance of inflicting more injury on the victim through revictimization. The healthcare provider’s understanding of the signs of verbal and nonverbal cues, and their response by following predetermined protocols for identification, treatment, and appropriate referrals are essential elements of care of the trafficked victim. Care for the human trafficking victim involves an interdisciplinary, collaborative approach. Safety, transparency, and collaboration with peers and agencies are vital to successful rehabilitation of the trafficked victim. It is essential that the approach accounts for culture and gender equality, LGBTQ considerations and support, and most importantly, an empowering environment that assists the trafficking survivor the survivor to become a productive, functioning member of the community.

- Albright E, D’Adamo K. Decreasing Human Trafficking through Sex Work Decriminalization. AMA J Ethics. 2017 Jan 01;19(1):122-126. [

- Austin A, Herrick H, Proescholdbell S. Adverse Childhood Experiences Related to Poor Adult Health Among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Individuals. Am J Public Health. 2016 Feb;106(2):314-20.

- Cardoso JB, Brabeck K, Stinchcomb D, Heidbrink L, Price OA, Gil-García ÓF, Crea TM, Zayas LH. Integration of Unaccompanied Migrant Youth in the United States: A Call for Research. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2019;45(2):273-292.

- Cimino AN, Madden EE, Hohn K, Cronley CM, Davis JB, Magruder K, Kennedy MA. Childhood Maltreatment and Child Protective Services Involvement Among the Commercially Sexually Exploited: A Comparison of Women Who Enter as Juveniles or as Adults. J Child Sex Abus. 2017 Apr;26(3):352-371.

- Daley D, Bachmann M, Bachmann BA, Pedigo C, Bui MT, Coffman J. Risk terrain modeling predicts child maltreatment. Child Abuse Negl. 2016 Dec;62:29-38.

- Felitti VJ. Health Appraisal and the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study: National Implications for Health Care, Cost, and Utilization. Perm J. 2019;23:18-026.

- Fraley HE, Aronowitz T, Stoklosa HM. Systematic Review of Human Trafficking Educational Interventions for Health Care Providers. West J Nurs Res. 2020 Feb;42(2):131-142.

- Fraley HE, Aronowitz T. The Peace and Power Conceptual Model: An Assessment Guide for School Nurses Regarding Commercial Sexual Exploitation of Children. Nurs Sci Q. 2017 Oct;30(4):317-323.

- Geynisman-Tan JM, Taylor JS, Edersheim T, Taubel D. All the darkness we do not see. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017 Feb;216(2):135.e1-135.e5.

- Goodwin M. Vulnerable Subjects: Why Does Informed Consent Matter? J Law Med Ethics. 2016 Sep;44(3):371-80.

- Gordon M, Fang S, Coverdale J, Nguyen P. Failure to Identify a Human Trafficking Victim. Am J Psychiatry. 2018 May 01;175(5):408-409.

- Greenbaum J, Stoklosa H. The healthcare response to human trafficking: A need for globally harmonized ICD codes. PLoS Med. 2019 May;16(5):e1002799.

- Greenbaum VJ, Livings MS, Lai BS, Edinburgh L, Baikie P, Grant SR, Kondis J, Petska HW, Bowman MJ, Legano L, Kas-Osoka O, Self-Brown S. Evaluation of a Tool to Identify Child Sex Trafficking Victims in Multiple Healthcare Settings. J Adolesc Health. 2018 Dec;63(6):745-752.

- Hossain M, Zimmerman C, Abas M, Light M, Watts C. The relationship of trauma to mental disorders among trafficked and sexually exploited girls and women. Am J Public Health. 2010 Dec;100(12):2442-9.

- Iglesias-Rios L, Harlow SD, Burgard SA, Kiss L, Zimmerman C. Mental health, violence, and psychological coercion among female and male trafficking survivors in the greater Mekong sub-region: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychol. 2018 Dec 12;6(1):56.

- Islam MS. An assessment of child protection in Bangladesh: How effective is NGO-led Child-Friendly Space? Eval Program Plann. 2019 Feb;72:8-15.

- Jensen C. Toward evidence-based anti-human trafficking policy: a rapid review of CSE rehabilitation and evaluation of Indian legislation. J Evid Inf Soc Work. 2018 Nov-Dec;15(6):617-648.

- Kelly MA, Bath EP, Godoy SM, Abrams LS, Barnert ES. Understanding Commercially Sexually Exploited Youths’ Facilitators and Barriers Toward Contraceptive Use: I Didn’t Really Have a Choice. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019 Jun;32(3):316-324.

- Kiss L, Zimmerman C. Human trafficking, and labor exploitation: Toward identifying, implementing, and evaluating effective responses. PLoS Med. 2019 Jan;16(1):e1002740.

- Leong FTL, Pickren WE, Vasquez MJT. APA efforts in promoting human rights and social justice. Am Psychol. 2017 Nov;72(8):778-790.

- Leslie J. Human Trafficking: Clinical Assessment Guideline. J Trauma Nurs. 2018 Sep/Oct;25(5):282-289.

- Long E, Dowdell EB. Nurses’ Perceptions of Victims of Human Trafficking in an Urban Emergency Department: A Qualitative Study. J Emerg Nurs. 2018 Jul;44(4):375-383.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Caring for the Trafficked Patient: Ethical Challenges and Recommendations for Health Care Professionals. AMA J Ethics. 2017 Jan 01;19(1):80-90.

- Macias-Konstantopoulos WL. Diagnosis Codes for Human Trafficking Can Help Assess Incidence, Risk Factors, and Comorbid Illness and Injury. AMA J Ethics. 2018 Dec 01;20(12):E1143-1151.

- Menon B, Stoklosa H, Van Dommelen K, Awerbuch A, Caddell L, Roberts K, Potter J. Informing Human Trafficking Clinical Care Through Two Systematic Reviews on Sexual Assault and Intimate Partner Violence. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2018 Nov 19;1524838018809729.

- Metcalf EP, Selous C. Modern slavery response and recognition training. Clin Teach. 2020 Feb;17(1):47-51.

- Mostajabian S, Santa Maria D, Wiemann C, Newlin E, Bocchini C. Identifying Sexual and Labor Exploitation among Sheltered Youth Experiencing Homelessness: A Comparison of Screening Methods. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019 Jan 28;16(3)

- Murray A, Smith L. Implementing Evidence-Based Care for Women Who Have Experienced Human Trafficking. Nurs Womens Health. 2019 Apr;23(2):98-104.

- Nsonwu M. Human Trafficking of Immigrants and Refugees in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2019 Mar-Apr;80(2):101-103.

- Powell C, Dickins K, Stoklosa H. Training US health care professionals on human trafficking: where do we go from here? Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1267980.

- Preble KM, Black BM. Influence of Survivors’ Entrapment Factors and Traffickers’ Characteristics on Perceptions of Interpersonal Social Power During Exit. Violence Against Women. 2020 Jan;26(1):110-133.

- Reap VJ. Sex Trafficking: A Concept Analysis for Health Care Providers. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2019 Apr/Jun;41(2):183-188.

- Reid JA, Baglivio MT, Piquero AR, Greenwald MA, Epps N. Human Trafficking of Minors and Childhood Adversity in Florida. Am J Public Health. 2017 Feb;107(2):306-311.

- Reid JA, Baglivio MT, Piquero AR, Greenwald MA, Epps N. No youth left behind to human trafficking: Exploring profiles of risk. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(6):704-715.

- Reid JA. Entrapment and Enmeshment Schemes Used by Sex Traffickers. Sex Abuse. 2016 Sep;28(6):491-511.

- Rollins R, Gribble A, Barrett SE, Powell C. Who is in Your Waiting Room? Health Care Professionals as Culturally Responsive and Trauma-Informed First Responders to Human Trafficking. AMA J Ethics. 2017 Jan 01;19(1):63-71.

- Rothman EF, Farrell A, Bright K, Paruk J. Ethical and Practical Considerations for Collecting Research-Related Data from Commercially Sexually Exploited Children. Behav Med. 2018 Jul-Sep;44(3):250-258.

- Rothman EF, Stoklosa H, Baldwin SB, Chisolm-Straker M, Kato Price R, Atkinson HG., HEAL Trafficking. Public Health Research Priorities to Address US Human Trafficking. Am J Public Health. 2017 Jul;107(7):1045-1047.

- Sabella D. PTSD among our returning veterans. Am J Nurs. 2012 Nov;112(11):48-52.

- Sabella D. The role of the nurse in combating human trafficking. Am J Nurs. 2011 Feb;111(2):28-37; quiz 38-9.

- Scannell M, MacDonald AE, Berger A, Boyer N. Human Trafficking: How Nurses Can Make a Difference. J Forensic Nurs. 2018 Apr/Jun;14(2):117-121.

- Shah D. Women’s rights in Asia and elsewhere – a fact or an illusion? Climacteric. 2019 Jun;22(3):283-288.

- Stoklosa H, MacGibbon M, Stoklosa J. Human Trafficking, Mental Illness, and Addiction: Avoiding Diagnostic Overshadowing. AMA J Ethics. 2017 Jan 01;19(1):23-34.

- Stuckler D, Steele S, Lurie M, Basu S. Introduction: ‘dying for gold’: the effects of mineral miningon HIV, tuberculosis, silicosis, and occupational diseases in southern Africa. Int J Health Serv. 2013;43(4):639-49.

- Teh LCL, Caddell R, Allison EH, Finkbeiner EM, Kittinger JN, Nakamura K, Ota Y. The role of human rights in implementing socially responsible seafood. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0210241.

- Vanwesenbeeck I. Sex Work Criminalization Is Barking Up the Wrong Tree. Arch Sex Behav. 2017 Aug;46(6):1631-1640.

- Viergever RF, Thorogood N, van Driel T, Wolf JR, Durand MA. The recovery experience of people who were sex trafficked: the thwarted journey towards goal pursuit. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019 Jan 22;19(1):3.

- Waugh L. Human Trafficking and the Health Care System. NCSL Legisbrief. 2018 Apr;26(14):1-2.

- Wyatt TR, Sinutko J. Hidden in Plain Sight: A Guide to Human Trafficking for Home Healthcare Clinicians. Home Healthc Now. 2018 Sep/Oct;36(5):282-288.