Contact Hours: 2

This online independent study activity is credited for 2 contact hours at completion.

Course Purpose

To provide healthcare providers with an overview of child abuse and pediatric abusive head trauma as required by New York State.

Overview

Child abuse and neglect are serious public health concerns. It involves the emotional, sexual, physical abuse, or neglect of a child under the age of 18 by a parent, custodian, or caregiver that results in potential harm, actual harm, or a threat of harm. Physical abuse can result in pediatric head trauma; namely shaken baby syndrome, which in severe cases, has a 20 % mortality rate. Victims of child abuse are often brought to healthcare facilities for treatment, however often, the ailments of the child are not identified as potential child abuse. This independent study provides an overview of child abuse and pediatric abusive head trauma, and the New York regulations for reporting such abuse.

Objectives

By the end of this learning activity, the learner will be able to:

- Identify the risk factors, signs, and symptoms of child abuse

- Define pediatric head trauma

- Describe common diagnostic tools and exams as they relate to child abuse and pediatric head trauma

- Describe the legal reporting requirements of child abuse in the state of New York

Policy Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of FastCEForLess.com. If you want to review our policy, click here.

Disclosures

Fast CE For Less, Inc. and its authors have no disclosures. There is no commercial support.

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.

| Child abuse | Involves the emotional, sexual, physical, or neglect of a child under the age of 18 by a parent, custodian, or caregiver that results in potential harm, harm, or a threat of harm. |

| Domestic violence | The victimization of an individual with whom the abuser has an intimate or romantic relationship. It includes physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive acts) by a current or former intimate partner. |

| Emotional abuse | Refers to behaviors that harm a child’s self-worth or emotional well-being. Examples include name calling, shaming, rejection, withholding love, and threatening. |

| Munchausen by proxy syndrome | Factitious disorder where an individual fabricates or exaggerates mental or physical health problems in the person for whom he or she cares. The primary motive is to gain attention or sympathy for themselves. |

| Neglect | The failure to meet a child’s basic physical and emotional needs. These needs include housing, food, clothing, education, and access to medical care. |

| Physical abuse | The intentional use of physical force that can result in physical Examples include hitting, kicking, shaking, burning, or other shows of force against a child. Examples include: Assault Biting Burning Choking Gagging Grabbing Kicking Punching Pulling hair Restraining Scratching Shaking Shoving Slapping |

| Sexual abuse | Involves pressuring or forcing a child to engage in sexual acts. It includes behaviors such as fondling, forced anal, oral, or vaginal penetration and exposing a child to other sexual activities. |

| The Cycle of Abuse and Violence | Begins with verbal threats that escalate to physical violence. Violent events are often unpredictable, and the triggers are unclear to the victims. The victims live in constant fear of the next violent attack. Violence and abuse are perpetrated in an endless cycle involving three phases: tension-building, explosive, and honeymoon. · Tension-building: In the tension-building phase, the abuser becomes more judgmental, temperamental, and upset; the victim may feel she is ”walking on eggshells.” Eventually, the tension builds to the point that the abuser explodes. During this phase, the victim may try to calm, stay away, or reason with the abuser, often to no avail. The abuser is often moody, unpredictable, screams, threatens, and intimidates. They may use children as tools to intimidate the victim and family. They often engage in alcohol and illicit drug use. · Explosive: The explosive phase involves the victim attempting to protect themselves and the family, possibly by contacting authorities. This phase may result in injuries to the victim. The abuser may start with breaking items that progress to striking, choking, and rape. The victim may be imprisoned. Emotional, verbal, physical, financial, and sexual abuse is common. · Honeymoon: During the honeymoon phase, the victim may set up counseling, seek medical attention, and agree to stop legal proceedings. They may hold the mistaken belief and hope that the situation will not happen again. Unfortunately, this is rarely the case. The abuser may apologize, agree to counseling, beg forgiveness, and give presents. They may declare love for the victim and family and promise to “never do it again.” |

Family and Domestic violence are a common problem in the United States and affects approximately 10 million people every year. They are abusive behaviors in which one individual gains power over another individual. Domestic and family violence occurs in all ages, races, and sexes. It knows no cultural, educational, geographic, religious, or socioeconomic limitation. Domestic and family violence includes child abuse, intimate partner abuse, and elder abuse and encompasses economic, physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse toward children, adults, and elders. ⁴˒⁵ It causes diminished psychological and physical health and decreases the quality of life.

Child abuse and neglect are serious public health concerns. Child abuse includes all four types of abuse and neglect against a child under the age of 18 by a parent, caregiver, or another person in a custodial role that results in harm, potential for harm, or threat of harm to a child. The four common types of abuse and neglect include emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect.

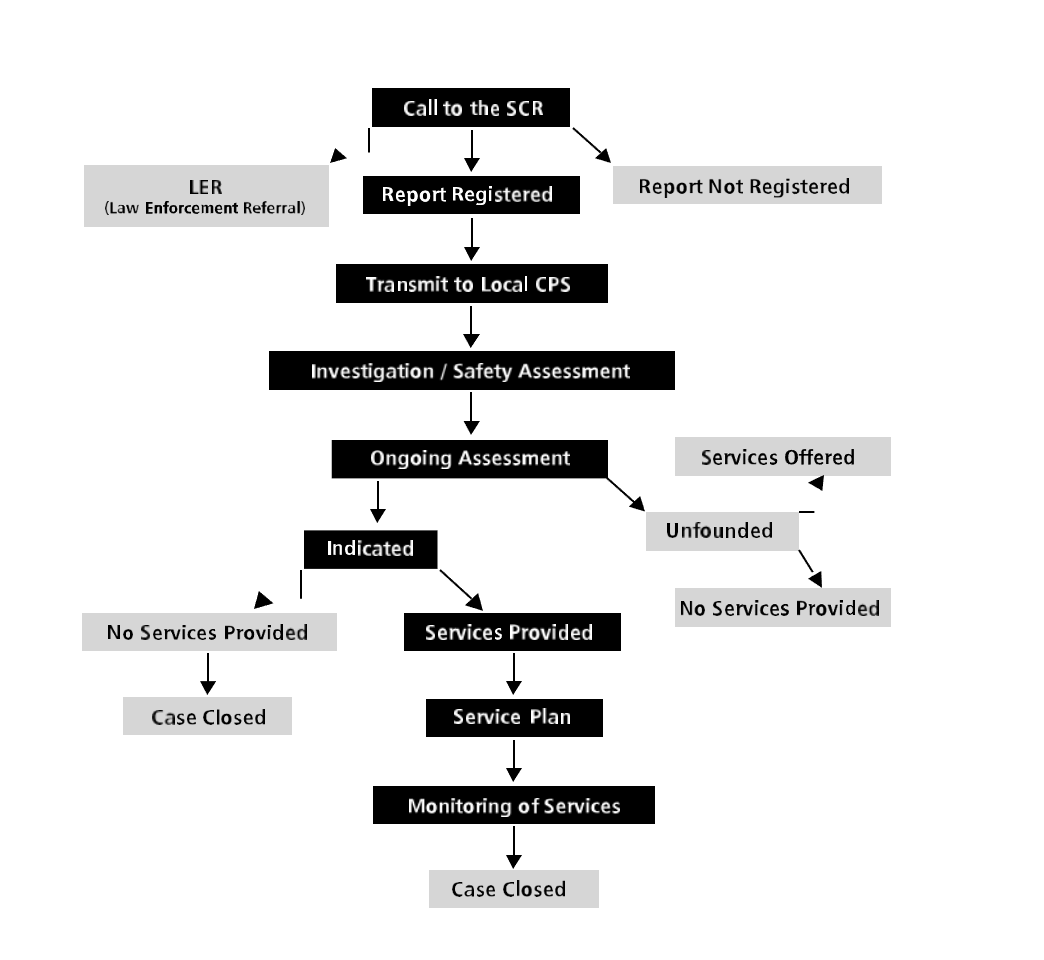

In the 1980s, a national study was conducted and concluded that many professionals did not report abuse and maltreatment because of a lack of knowledge in recognizing warning signs and clues of abuse, and confusion regarding the reporting laws and procedures. In 1999, the Monroe County Department of Social Services engaged the University of Rochester’s Department of Community and Preventive Medicine and the Perinatal Network of Rochester to conduct research for a campaign to increase community involvement to prevent child abuse and maltreatment, and to improve reporting. Mandated reporters were included as a group in this study. As a result of these and other studies, there is evidence that child abuse and maltreatment are underreported and that, conversely, some situations that are reported to the New York State Central Register (SCR) are more suitable for preventive services or other resources. The purpose of this training is to provide the learner the knowledge to make an informed decision about whether a situation involves child abuse or maltreatment, what the reporting obligation is, and how to go about making such a report. This training is designed to provide an understanding of the preventive-protective continuum of care within the Child Protective Services (CPS) system as it operates in New York State.

Domestic and family violence, including child abuse often starts when a caretaker or parent feels the need to dominate or control a child. This can occur because of several reasons, such as:

- Alcohol and drugs use, as an impaired individual may be less likely to control violent impulses

- Anger management issues

- Learned behavior from growing up in a family where domestic violence was accepted

- Personality disorder or psychological disorder

While the research is not definitive, several characteristics are thought to be present in perpetrators of child abuse. Abusers tend to:

- Be nonbiological, transient caregivers in the home, such as a parent’s significant other

- Have a history of substance abuse and/or mental health issues including depression in the family

- Have a parental history of child abuse and or neglect

- Have parental characteristics such as young age, low education, single parenthood, large number of dependent children, and low income

- Have thoughts and emotions that tend to support or justify maltreatment behaviors

- Lack understanding of children’s needs, child development and parenting skills

There are several risk factors for child abuse, which are inclusive of individual, family, and community issues. For instance, there is a correlating relationship between parental stress and child abuse. The more stress a parent experiences, such as with separation or divorce, the more likely they will be involved in child abuse.

Exposure to domestic abuse and family violence as a child is commonly associated with becoming a perpetrator of domestic violence as an adult. This cycle occurs because children who are victims or witness domestic and family violence may believe that violence is a reasonable way to resolve a conflict. As a child grows to become an adult, they may solve conflicts in a manner that is familiar to them, often resulting in a repeated cycle of domestic violence. Males who learn that females are not equally respected are more likely to abuse females in adulthood. Females who witness domestic violence as children are more likely to be victimized by their spouses. While females are often the victim of domestic violence, the gender roles can be reversed. Perpetrators of domestic violence commonly repeat acts of violence with new partners, and drug and alcohol abuse greatly increase these risks. ¹⁴ Common risk factors for domestic violence include:

- A family history of violence

- Aggressive behavior as a youth

- Antisocial personality disorder

- Corporal punishment in the household

- Domination, which may include emotional, physical, or sexual abuse that may be caused by an interaction of situational and individual factors. This means the abuser learns violent behavior from their family, community, or culture. They see violence and are victims of violence.

- Economic stress in families with low annual incomes

- Females whose educational or occupational level is higher than their spouse’s

- History of abuse as children

- Individuals with disabilities

- Low education

- Low self-esteem

- Marital discord

- Marital infidelity

- Multiple children

- Poor legal sanctions or enforcement of laws

- Poor parenting

- Pregnancy

- Psychiatric history

- The use and abuse of alcohol and drugs are strongly associated with a high probability of violence. Alcohol abuse is known to be a strong predictor of acute injury.

- Unemployment

Abuse usually begins with emotional or verbal threats and may escalate to physical violence. Victims of child abuse live in a constant state of fear. Often, the abuser can become explosively violent. After the violent event, the abuser may apologize. This cycle usually repeats in child abuse. ¹¹˒¹²˒¹³ No matter the underlying circumstances, nothing justifies child abuse. Understanding the causes assists in understanding the behavior of an abuser. The abuser must be separated from the potential victim and treated for destructive behavior before a major event negatively impacts the lives of all involved.

At least 14% of children have experienced child abuse and/or neglect in the past year, and due to barriers/lack of reporting, this is likely an underestimate. Rates of child abuse and neglect are 5 times higher for children in families with low socio-economic status compared to children in families with higher socio-economic status. In 2018, nearly 1,770 children died of abuse and neglect in the United States. The total lifetime economic burden associated with child abuse and neglect is approximately $428 billion. This economic burden is like the costs of other public health problems, such as type 2 diabetes and stoke.

Each year, pediatric head trauma results in over 500,000 emergency department visits and about 60,000 hospitalizations in the United States. ¹ Fatal head trauma in children is mainly caused by abuse. Falls and sports/recreation-related head injuries rarely cause fatal injuries but can cause post-concussive symptoms in up to 30% of children. Falls are more common in children 0 to 4-years of age, while sports and recreation-related injuries are more common in children 5 to 14-years of age.

Victims of alleged child abuse or neglect have specialized needs during the assessment process. The Joint Commission requires hospitals to have policies for the identification, evaluation, management, and referral of victims. This includes:

- Safeguarding information and potential evidence that may be used in future actions as part of the legal process.

- Having policies and procedures that define responsibility for collecting these materials.

- Having policies that define activities and specify who is responsible for their implementation.

- Provide an opportunity for victims of domestic violence to obtain help.

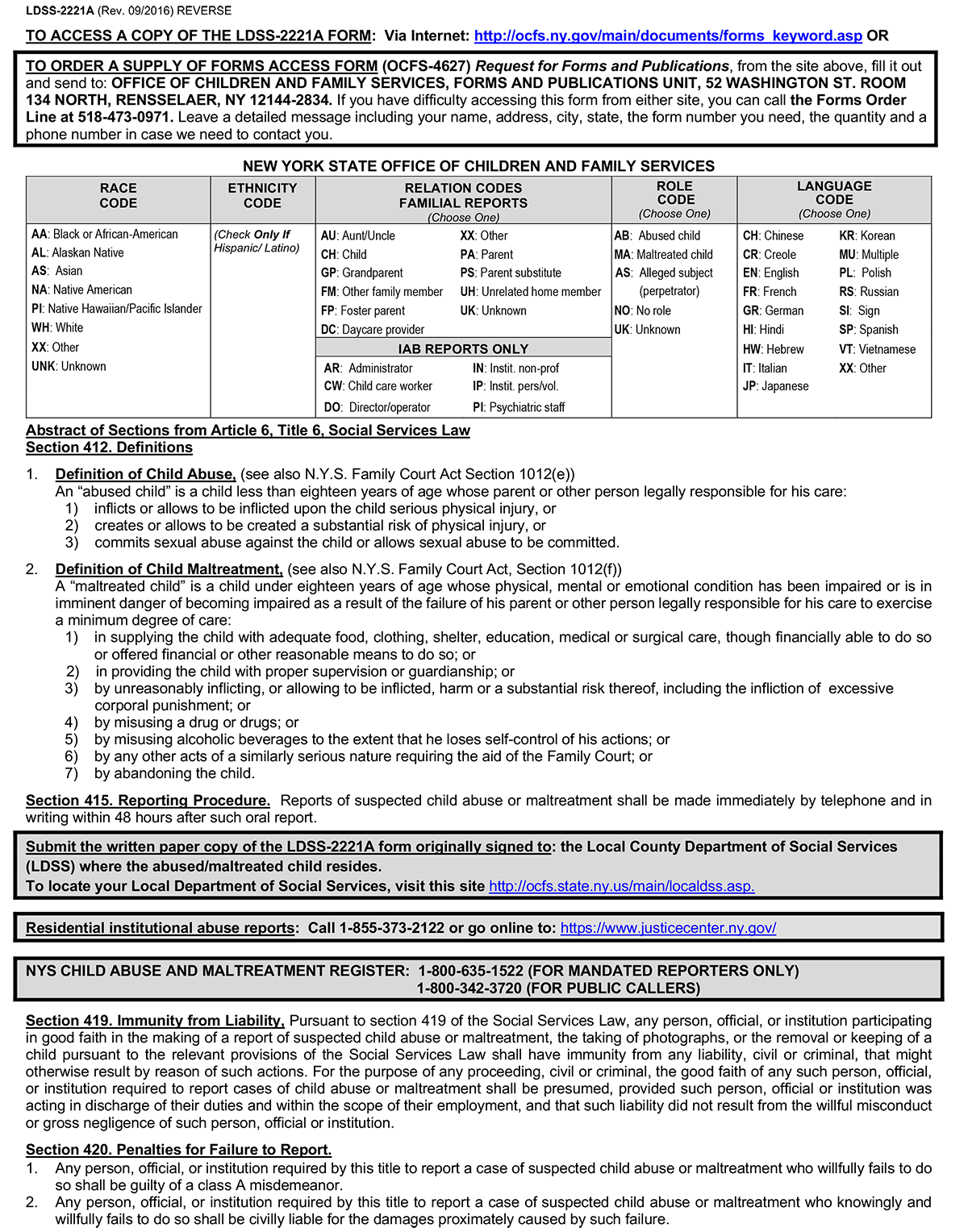

The laws that guide New York Child Protective Services today are Article 6, Title 6 of the Social Services Law and Article 10 of the Family Court Act, including:

- Section 413 of the Social Service Law requires designated professionals to report to the SCR when they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child before them in their professional capacity has been abused or maltreated. Or, when there is reasonable cause to suspect that a child is an abused or maltreated child where the parent, guardian, custodian, or other person legally responsible for such child comes before them in their professional official capacity and states from personal knowledge, facts, conditions, or circumstances which, if correct, would render the child an abused or maltreated child, then they must report.

- Whenever such person is required to report as a member of the staff of a medical or other public or private institution, school, facility, or agency, they must make the report as required by this title.

- Nothing in this section or title is intended to require more than one report from any institution, school, or agency.

- No retaliatory personnel action is allowed.

There are three components to the legal framework applicable to mandated reporters:

Immunity from Liability

Some mandated reporters face a conflict between their legal obligation to report and, their legal obligation to maintain client or patient confidentiality. Section 419 of the Social Service Law provides immunity from liability for mandated reporters. Mandated reporters are immune from any criminal or civil liability if the report was made in good faith. The good faith of such a person, official, or institution required to report is presumed. This means if a person accuses the mandated reporter of making a false report in bad faith, they must prove that they acted with gross negligence or willful misconduct.

Confidentiality

- New York State law provides confidentiality to those who make a report.

- OCFS and the local CPS are not permitted to release to the subject of the report any data that would identify the source of the report, unless the reporter has given written permission for OCFS or CPS to do so.

- Information regarding the report source may be shared by OCFS or the local CPS with certain individuals (e.g., courts, police, district attorney), but only as provided by law.

Penalties for Failure to Report

- Mandated reporters are subject to serious consequences for failure to report.

- A mandated reporter who fails to report can be found guilty of a Class A misdemeanor. A Class A misdemeanor can result in a penalty of up to a year in jail, a fine of up to $1,000.00, or both. Additionally, failing to report may result in a lawsuit in civil court for monetary damages for any harm caused by the mandated reporter’s failure to make the report to the SCR, including wrongful death suits. No medical or other public or private institution, school, facility, or agency shall take any retaliatory personnel action against an employee who made a report to the SCR. No school, school official, childcare provider, foster care provider, residential care facility provider, hospital, medical institution provider, or mental health facility provider shall impose any conditions, including prior approval or prior notification, upon a member of their staff mandated to report suspected child abuse or maltreatment.

- Class A misdemeanor, which can result in a penalty of up to a year in jail, a fine of $1,000, or both.

- Additionally, failing to report may result in a lawsuit in Civil Court for monetary damages for any harm caused by the mandated reporter’s failure to make the report to the SCR, including wrongful death suits.

- Mandated Reporters must call the SCR to ensure immunity and to be protected from criminal and civil liability. If the mandated reporter calls the local county department of social services office or a law enforcement official, then that mandated reporter has not fulfilled their legal duty to report to the SCR.

Effective November 21, 2005, an amendment to SSL §415 requires mandated reporters who make a report that initiates an investigation of an allegation of child abuse or maltreatment to comply with all requests for records made by CPS relating to such report. The mandated reporter to whom the request is directed makes the determination of what information is essential. If CPS believes that the mandated reporter has additional essential information pertaining to the report, CPS should ask the mandated reporter for the additional records and attempt to come to agreement regarding any additional records. If CPS and the mandated reporter cannot come to agreement and CPS disagrees with the mandated reporter’s rationale for why the records are not relevant to the report, CPS may seek a court order pursuant to CPLR Article 31 and SSL §415 directing the mandated reporter to produce the essential information. The amendment to SSL §415 only applies to the records of the mandated reporter who made the report of suspected child abuse or maltreatment. Additionally, the records that CPS requests should be limited only to information that directly pertains to the report itself. The purpose of the inclusion of these records is to support a full investigation of allegations of child abuse or maltreatment. This language is not intended to be an expansion of a mandated reporter’s current obligation. Since the passage of the federal HIPAA, confusion has arisen regarding the obligation of a mandated reporter to provide copies of written records that underlie the report. The intent of the amendment to SSL 415 is to make clear that the mandated reporter’s obligation also extends to the provision of the records necessary to investigate the report, as has always been the case.

Materials included are:

- Records relating to diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment

- Clinical records of any patient or client

- Written reports from mandated reporters shall be admissible in evidence in any proceedings relating to child abuse or maltreatment.

- The statutory amendments do not require written consent and are intended to promote CPS getting the needed supplemental information that supports the initial report.

The Abandoned Infant Protection Act (AIPA) does not affect responsibilities as a mandated reporter. The AIPA does not amend the law regarding mandated reporters and does not in any way change or lessen the responsibilities of mandated reporters. Mandated reporters who learn of abandonment are still obligated to fulfill their legal responsibility. The SCR only registers reports against a parent, guardian, or other person eighteen years of age or older who is legally responsible for the child. According to the Family Court Act, persons legally responsible include the child’s custodian, guardian, and any other person 18-years old or older responsible for the child’s care at the relevant time. This includes any person continually or at regular intervals found in the same household as the child when the conduct of such person causes or contributes to the abuse or maltreatment of the child. Once the SCR registers a report, the person who is named as causing the harm to the child becomes the “subject of the report.” Teachers in most public or private schools do not qualify as “subjects of reports” when they are acting as teachers. Teachers can be “subjects of reports” when the incident involves their own child or with a child they have legal responsibility for outside of their role as a teacher.

Nothing in this section or title is intended to require more than one report from any institution, school, or agency. No retaliatory personnel action is allowed.

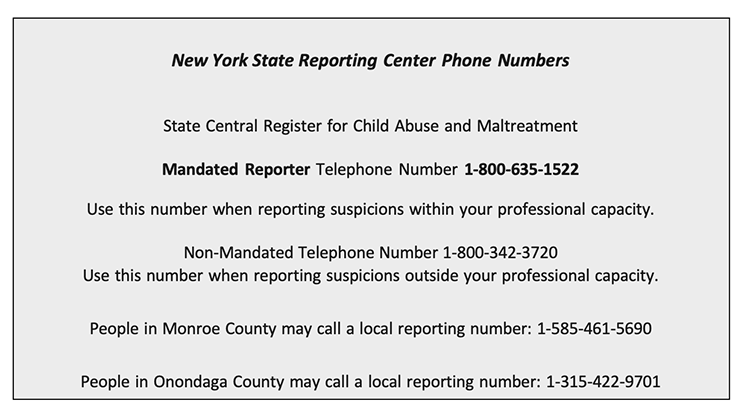

Oral reports must be made to the SCR by calling the mandated reporter designated hotline. Calls to this hotline are given priority. The mandated reporter hotline should not be given to anyone who is not a mandated reporter. This circumvents the intent of the mandated reporter hotline.

The mandated reporter hotline number is 1-800-635-1522.

If a mandated reporter is notacting in their official capacity when the call is made, then they must call the non-mandated reporter hotline phone number.

The non-mandated reporter hotline number is 1-800-342-3720.

Two counties in New York State have their own localized hotlines that may be used instead of the SCR hotline.

Onondaga County (315)-422-9701

Monroe County (585)-461-5690

New York State Office of Children and Family Services

518-473-7793

http://www.ocfs.state.ny.us/main/

Prevent Child Abuse New York Helpline

English and Spanish

800-342-7472 – 24 hrs.

www.preventchildabuseny.org

New York State Domestic Violence Hotline

800-942-6906 English

800-942-6908 Spanish

www.opdv.state.ny.us

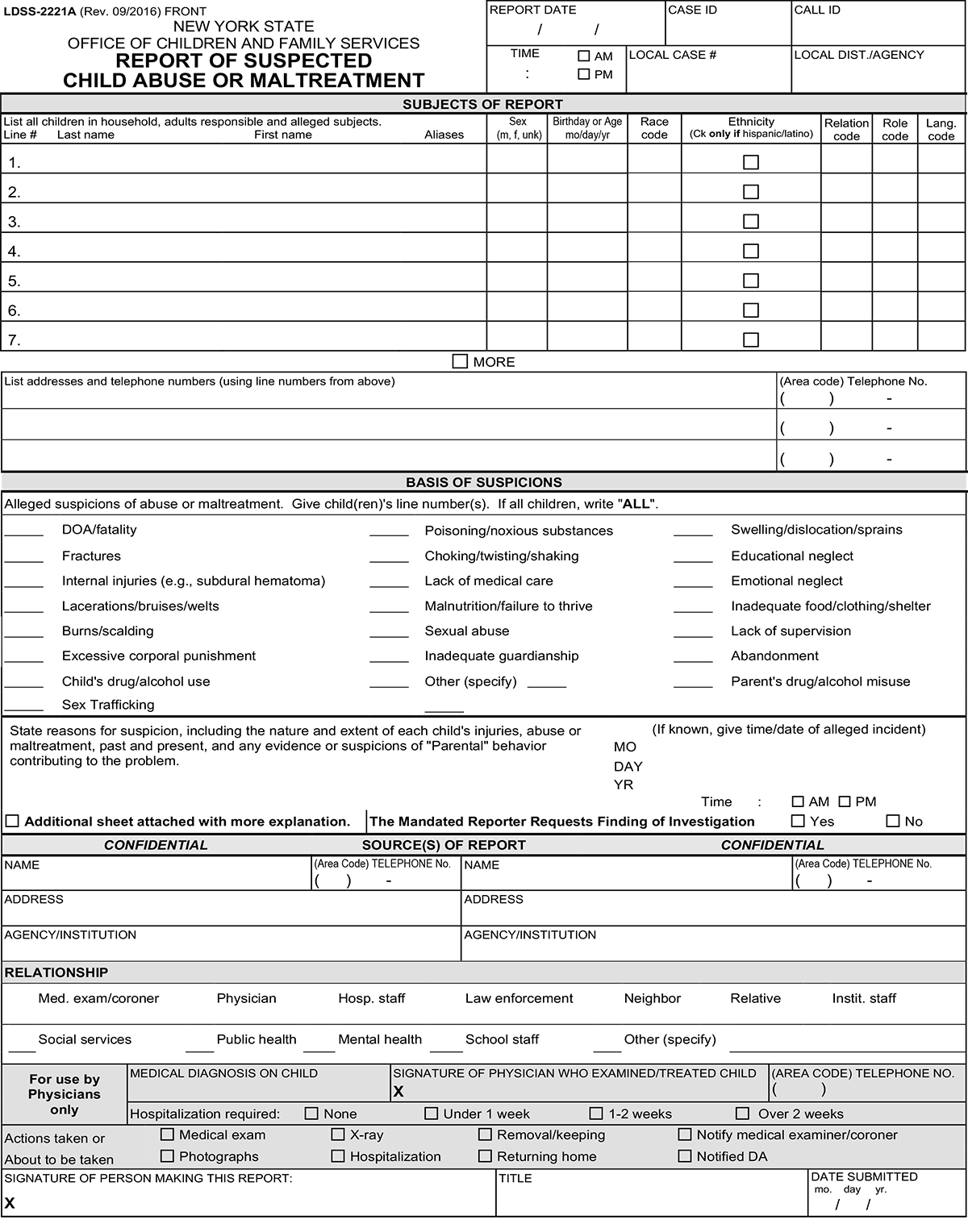

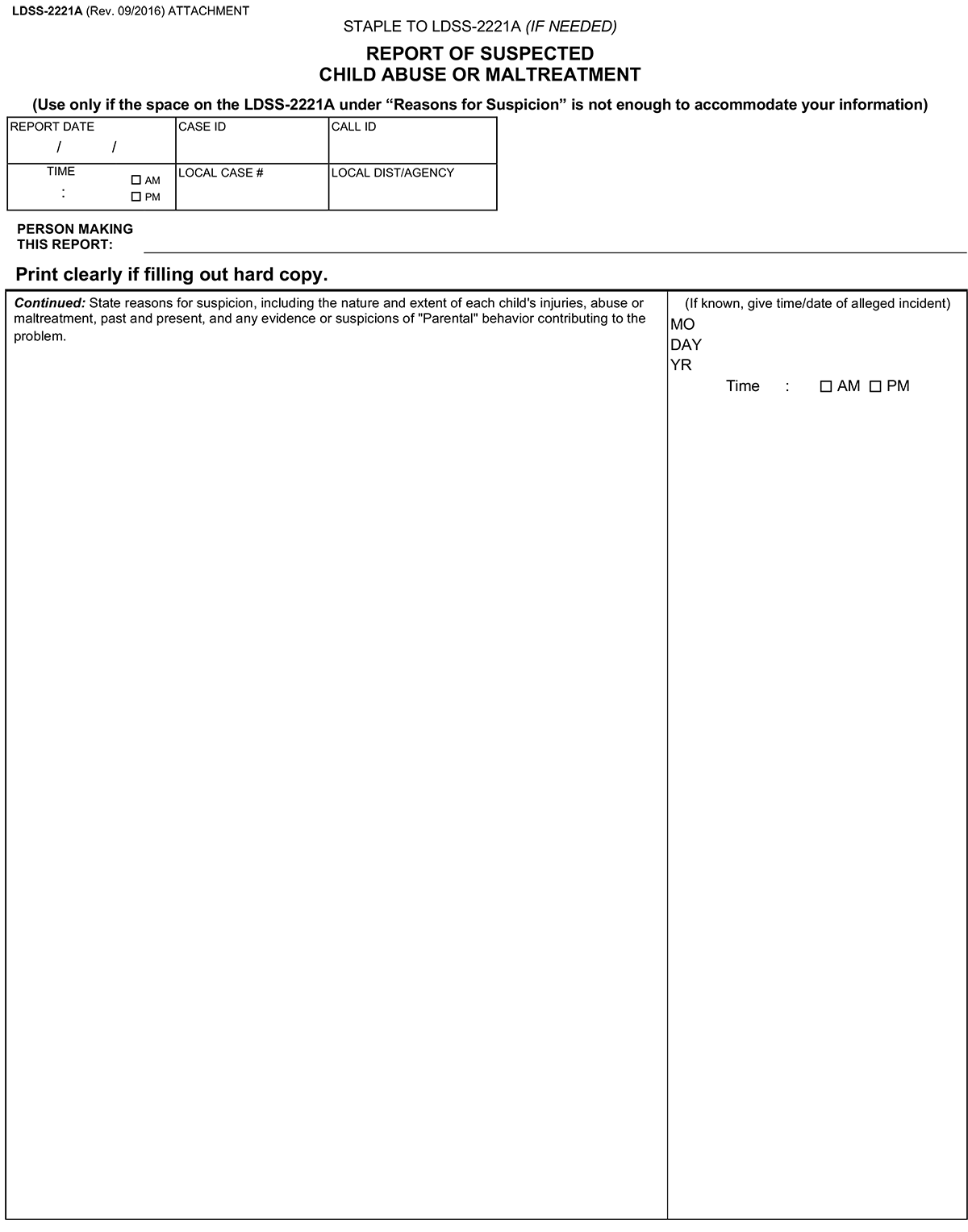

The mandated reporter should use the LDSS-2221A form to gather information, and then use it as a tool to organize the information while making the call.

If the SCR accepts the report, the mandated reporter should write down the call identification (ID) number given by the CPS Specialist at the SCR. On the upper right corner of the 2221A there is a place to record the call ID number. Two copies of the form, an original and a duplicate must be forwarded to the local CPS agency within 48 hours. A third copy should be kept on file by the reporter.

When the circumstances of the mandated reporter’s call to the SCR constitute a crime or an immediate threat to the child’s health or safety, but the report is not registerable, the SCR will send the information to the New York State Police Information Network (NYSPIN), or to the New York City Police Department (NYPD) for necessary action.

These types of calls are referred to as Law Enforcement Referrals, or “LERs.” They are transmitted to the appropriate police agency for follow-up. They are not registered SCR reports. LERs are not assigned a call identification number. If the mandated reporter is in a LER situation, they do not need to complete the LDSS-2221A form.

After the mandated reporter completes their call to the SCR, they must immediately notify the person in charge of the institution, school, facility, or agency, or the designated agent of the person in charge, and provide the information reported to the SCR, including the names of other persons identified as having direct knowledge or the alleged abuse or maltreatment and other mandated reporters identified as having reasonable cause to suspect.

The person in charge or designated agent, once notified that a report has been made to the SCR, becomes responsible for all subsequent administration concerning the report, including preparation and submission of the form LDSS-2221A.

As suggested earlier, if time permits, it may be helpful for the mandated reporter to fill out the form before placing their call to the SCR. This enables them to organize whatever demographic and identifying information they may have, as well as their allegations and concerns. The safety of the child must come before the completion of the form.

Written reports, using the LDSS-2221A, should be sent to the local CPS office within 48 hours of making the oral report.

Identifying a child of suspected abuse is difficult because the child may be nonverbal or too frightened or severely injured to talk. Also, the perpetrator will rarely admit to the injury, and witnesses are uncommon. Healthcare providers will see children of abuse in a range of ways that include:

- An adult or mandated reporter may bring the child in when they are concerned for abuse

- A child or adolescent may come in disclosing the abuse

- The perpetrators may be concerned that the abuse is severe and bring in the patient for medical care

- The child may present for care unrelated to the abuse, and the abuse may be found incidentally.

Physical abuse should be considered in the evaluation of all injuries of children. A thorough history of present illness is important to make a correct diagnosis. Important aspects of the history-taking involve gathering information about the child’s behavior before, during, and after the injury occurred. History-taking should include interviewing the verbal child and each caretaker separately. The verbal child and parent or caretaker should be able to provide their history without interruptions in order not to be influenced by the healthcare provider’s questions or interpretations.

| Abusive Head Trauma: | Abusive head trauma (AHT), also known as the shaken baby syndrome (SBS), is a preventable, severe form of physical child abuse resulting from violently shaking an infant or toddler by the shoulders, arms, or legs. Shaken baby syndrome and the resultant head injury has leading cause of death related to child abuse; nearly 25%. Symptoms may be as subtle as vomiting, or as severe as lethargy, seizures, apnea, or coma. Findings suggestive of AHT are retinal hemorrhages, subdural hematomas, and diffuse axonal injury. An infant with abusive head trauma may have no neurologic symptoms and may be diagnosed instead with acute gastroenteritis, otitis media, GERD, colic, and other non-related entities. Often, a head ultrasound is used as the initial evaluation in young infants. However, it is not the test of choice in the emergency setting. In the assessment of AHT, the ophthalmologic examination should be performed, preferably by a pediatric ophthalmologist. · The injuries seen in infants and toddlers with Abusive Head Trauma (AHT) may include: · Bleeding over the surface of the brain (subdural hemorrhages). · Other brain injuries, including brain swelling and injuries to the white matter of the brain. · Bleeding on the back surface of the eyes (retinal hemorrhages). · Some victims have evidence of blunt impact to the head; others do not. · Some victims have other evidence of physical abuse, including bruises, abdominal injuries, and recent or healing broken bones; other do not. Nearly all victims of AHT suffer serious, long-term health consequences. Examples include: · vision problems · developmental delays · physical disabilities · hearing loss It is the responsibility of every healthcare provider to play a role in preventing abusive head trauma. They must know the risk factors and the triggers for abuse, inform and teach the parent or caregiver the dangers of shaking or hitting a baby’s head, and identify support for the parents and caregivers in their community. When teaching the parent or caregiver about abusive head trauma, it is imperative that the healthcare provider ensures that the parent or caregiver: · Understands that infant crying is worse in the first few months of life but will get better as the child grows. · Understands that soothing a crying baby is not easy, but they can calm the baby by breastfeeding, offering a bottle or pacifier, singing, swaddling, taking the baby for a ride in the car or walk in the stroller, laying the baby across their lap on the baby’s stomach and gently rubbing or patting the baby’s back. · Calls a friend or relative, or use a parent helpline for support · Check for signs of illness and call the doctor if the child appears to be sick and will not stop crying. · Never leaves the baby with a person who is easily irritated, has a temper, or has a history of violence. |

| Abdominal Trauma: | Abdominal trauma is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in abused children. It is the second most common cause of death from physical abuse and is mostly seen in infants and toddlers. Many of these children will not display overt findings, and there may be no abdominal bruising on physical exam. Therefore, screening should include liver function tests, amylase, lipase, and testing for hematuria. Any positive result can indicate the need for imaging studies, particularly an abdominal computerized tomography (CT) scan. |

| Skeletal Trauma: | The second most common type of child abuse after neglect is physical abuse. Eighty percent of abusive fractures occur in non-ambulatory children, particularly in children younger than 18 months of age. The most important risk factor for abusive skeletal injury is age. There is no fracture pathognomonic for abuse, but there are some fractures that are more suggestive of abuse. These include posterior or lateral rib fractures and “corner” or “bucket handle” fractures, which occur at the ends of long bones and which result from a twisting mechanism. Other highly suspicious fractures are sternal, spinal, and scapular fractures. |

| Neglect: | The physical examination may not only demonstrate signs of physical abuse but may show signs of neglect. The general examination may show poor oral hygiene with extensive dental caries, malnutrition with significant growth failure, untreated diaper dermatitis, or untreated wounds. All healthcare providers are mandated reporters, and as such, they are required to make a report to child welfare when there is a reasonable suspicion of abuse or neglect. The healthcare provider does not need to be certain of child abuse to report it; they just must have a reasonable suspicion that it is occurring. This mandated report may be lifesaving for many children. An interprofessional approach with the inclusion of a child-abuse specialist is optimal. |

| Physical Abuse: | Child physical abuse should be considered in each of the following: · A non-ambulatory infant with any injury · Injury in a nonverbal child · Injury inconsistent with child’s physical abilities and a statement of harm from the verbal child · Mechanism of injury not plausible; multiple injuries, particularly at varying stages of healing · Bruises on the torso, ear, or neck in a child younger than 4 years of age · Burns to genitalia · Stocking or glove injury distributions or patterns · The parent or caregiver is unconcerned about the injury · There is an unexplained delay in seeking care · Inconsistencies or discrepancies in the history provided by the parent or caregiver. “TEN 4” is a useful mnemonic device used to recall which bruising locations are of concern in cases involving physical abuse: Torso, Ear, Neck and 4 (less than four years of age or any bruising in a child less than four months of age). A few injuries that are highly suggestive of abuse include retinal hemorrhages, posterior rib fractures, and classic metaphyseal lesions. Bruising is the most common sign of physical abuse but is missed as a sentinel injury in ambulatory children. Bruising in non-ambulatory children is rare and should raise suspicion for abuse. The most common areas of bruising in non-abused children are the knees and shins as well as bony prominences including the forehead. The most common area of bruising for the abused children includes the head and face. Burns are a common form of a childhood injury that is usually not associated with abuse. Immersion burns have characteristic sharp lines of demarcation that often involves the genitals and lower extremities in a symmetric pattern, and this is highly suspicious for abuse. |

| Sexual Abuse: | About 25% of girls and 8% of boys experience child sexual abuse at some point in childhood, and 91% of the abuse is perpetrated by someone the child or child’s family knows. Sexual abuse can affect how a child behaves, thinks, and feels over a lifetime. This can cause short and long-term emotional, behavioral, and physical health consequences. These consequences include: · Chronic health conditions later in life · depression · Increased risk for suicide or suicide attempts · Physical injuries · Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) · Risky sexual behaviors, · Substance abuse · Unwanted/unplanned pregnancies |

Another outcome commonly associated with child sexual abuse is an increased risk of re-victimization throughout a person’s life. If a child demonstrates behavior such as undressing in front of others, touching others’ genitals, as well as trying to look at others underdressing, there may be a concern for sexual abuse. It is important to understand that a normal physical examination does not rule out sexual abuse. In fact, most sexual abuse victims have a normal anogenital examination. In most cases, the strongest evidence that sexual abuse has occurred is the child’s statement.

Children who are abused may be unkempt and/or malnourished, and may also display inappropriate behavior such as aggression, being withdrawn, and have poor communication skills. Others may be disruptive or hyperactive. They also may have poor school attendance.

Specific injuries and associated findings of child abuse include:

| Bites | Chipped teeth |

| Cigarette or cigar burns | Craniofacial and neck injuries |

| Friction burns | Injuries at different stages of healing |

| Injuries to multiple organs | Intracranial hemorrhage |

| Long-bone fractures | Marks shaped like belt buckles and cords |

| Oral burns, contusions, or cuts | Patterned injuries |

| Poor dental health | Sexually transmitted diseases |

| Skull fractures | Strangulation injuries |

| Unusual injuries |

When considering child abuse, one must also identify differential diagnoses’ that may coincide with injuries. The diagnosis and injury type can vary with the child’s age. Various differential diagnosis’ and causes include:

| Head Trauma: | – Accidental injury – Arteriovenous malformations – Bacterial meningitis – Birth trauma – Cerebral sinovenous thrombosis – Hemophilia – Leukemia – Neonatal alloimmune thrombocytopenia – Metabolic diseases – Solid brain tumors – Unintentional asphyxia – Vitamin K deficiencies |

| Bruises and Contusions: | – Accidental bruises – Birth trauma – Bleeding disorder – Coining – Cupping – Congenital dermal melanocytosis (Mongolian spots) – Erythema multiforme – Hemangioma – Hemophilia – Hemorrhagic disease – Henoch-Schonlein purpura – Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura – Insect Bites – Malignancy – Nevi – Phytophotodermatitis – Subconjunctival hemorrhage from vomiting or coughing |

| Burns: | – Accidental burns – Atopic dermatitis – Contact dermatitis – Impetigo – Inflammatory skin conditions – Sunburn |

| Fractures: | – Accidental – Birth trauma – Bone fragility with chronic disease – Caffey disease – Congenital syphilis – Hypervitaminosis A – Malignancy – Osteogenesis imperfecta – Osteomyelitis – Osteopenia – Osteopenia of prematurity – Physiological subperiosteal new bone – Rickets – Scurvy – Toddler’s fracture |

When feasible, and without delaying care to the child, photographs of injuries should be taken prior to initiating treatment of suspected injuries of child abuse.

- Take an identification tag photo.

- Take photos from multiple injury angles and distances.

- Measure and document injury sizes.

- When photographing bite marks include photos focusing on each dental arch to avoid distortion.

- Check photos as they may be used in court.

The initial assessment should proceed in a stepwise fashion to identify all injuries, as well as optimize cerebral perfusion by maintaining hemodynamic stabilization and oxygenation in children with severe head trauma. The initial survey should also include a brief, focused neurological examination with attention to the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), pupillary examination, and motor function.

The pediatric GCS is like the adult GCS, but the main difference is in the verbal response assessment. It has also been modified to address age appropriate responses within the pediatric population. For instance, the pediatric GCS assigns a normal verbal score of 5 for babbling, cooing, or being oriented and using phrases appropriately, while subtracting 1 point if crying but consolable, using inappropriate words, or confusion, subtracting 2 points for inconsolable crying and incomprehensible words, subtracting 3 points for grunting or incomprehensible sounds, and subtracting 4 points for no verbal response.

After addressing any airway or circulatory deficits, a thorough head-to-toe physical examination must be performed with vigilance for occult injuries and careful attention to detect any of the following warning signs for head trauma:

| Base skull fracture: | Inspection for cranial nerve deficits, periorbital or postauricular ecchymosis, cerebrospinal fluid, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, hemotympanum |

| Increased intracranial pressure: | Fundoscopic examination for retinal hemorrhage (potential sign of abuse in children) and papilledema |

| Skull fractures: | Palpation of the scalp for hematoma, crepitus, laceration, and bony deformity (markers of skull fractures). In infants, fullness of the fontanelle can be a marker of intracranial hematoma or elevated increased intracranial pressure |

| Carotid or vertebral dissection: | Auscultation for carotid bruits, painful Horner syndrome or facial/neck hyperesthesia (markers of carotid or vertebral dissection) |

| Spinal cord injury: | Evaluation for cervical spine tenderness, paresthesia, incontinence, extremity weakness, priapism, and motor and sensory examination |

Laboratory studies are often important for forensic evaluation and criminal prosecution. On occasion, certain diseases may mimic findings that are like child abuse, and therefore, they must be ruled out.

| Urine: | A urine test may be used as a screen for sexually transmitted disease. If there is blood in the urine, bladder or kidney, trauma may be suspected. A urine toxicology test is indicated if there is evidence of altered level of consciousness, agitation, coma, or an apparent life-threatening event. It should also be ordered if a child was discovered in a dangerous environment, because up to 15% of victims of child abuse will have positive urine drug screens. Positive screens must be confirmed through blood analysis in cases of potential legal intervention. The chain of custody should be followed when sending a urine toxicology specimen to a laboratory. Confirmatory tests are usually sent to outside state-sponsored referral laboratories. |

| Hematology: | If the injuries on a child are consistent with a history of abuse, then it is unlikely that the injuries are the result of a bleeding disorder. Some tests can be falsely elevated, so a pediatrician who specializes in child abuse or a hematologist should review the results of the tests. Tests to assist in diagnosing a bleeding disorder include: · Complete blood cell count (CBC) · Platelet count · Prothrombin time · International Normalized Ratio · Partial thromboplastin time · Von Willebrand factor activity and antigen · Factors VIII and IX levels Laboratory evaluations that may be performed to rule out other diseases as causes of the injuries can include: · Bone injury: Calcium, magnesium, phosphate, alkaline phosphatase · Liver injury: Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase(ALT) · Metabolic injury: Glucose, blood urea nitrogen(BUN), creatinine, albumin, protein · Pancreas injury: Amylase and lipase |

| Gastrointestinal and Chest Trauma: | Children who experience abusive head trauma, fractures, nausea, vomiting, or an abnormal Glasgow Coma Scale score of less than 15 are the highest risk of domestic violence related health complications. In suspected gastrointestinal trauma, if the AST or ALT is greater than 80 IU/L, or lipase greater than 100 IU/L, an abdomen and pelvis CT with intravenous contrast should be performed. If there is any evidence of chest trauma, such as abrasions, bruises, rib fractures, clavicle fractures, sternal fractures, or a fractured sternum, a troponin level should be performed. If the results of the troponin test are elevated to greater than 0.04 ng/mL, a CT of the chest and an echocardiogram should be obtained. |

The evaluation of the pediatric skeleton can prove challenging for a non-specialist as there are subtle differences from adults and children, such as cranial sutures and incomplete bone growth. As a result, a fracture can be misinterpreted. When child abuse is suspected, a radiologist should be consulted to review the imaging results.

| Skeletal Survey: | A skeletal survey is indicated in children younger than two years with suspected physical abuse. The incidence of occult fractures is as high as 25% in physically abused children younger than two years. The healthcare provider should consider screening all siblings younger than two years. A skeletal survey consists of 21 dedicated views, as recommended by the American College of Radiology. The views include anteroposterior (AP) and lateral aspects of the skull; lateral spine; AP, right posterior oblique, left posterior oblique of chest/rib technique; AP pelvis; AP of each femur; AP of each leg; AP of each humerus; AP of each forearm; posterior and anterior views of each hand; AP (dorsoventral) of each foot. If the findings are abnormal or equivocal, a follow-up survey is indicated in 2 weeks to visualize healing patterns. A “babygram” that includes only one film of the entire body is not an adequate skeletal survey. Skeletal fractures will heal at different rates which are dependent on the age, location, and nutritional status of the child. · Soft tissue swelling is present at zero to 10 days. · Long bone fractures may take 10 to 21 days to form a soft callus. |

| Computed tomography scan (CT) scan: | If abuse or head trauma is suspected, a CT scan of the head should be performed on all children younger than 24 months if head trauma or intracranial injury is suspected. Healthcare providers should have a low threshold to obtain a CT scan of the head when abuse is suspected, especially in an infant younger than 12 months Non-contrast cranial computed tomography (CT) is the imaging modality of choice for children with head injuries and an abnormal Glasgow coma scale. Observing a midline shift, subarachnoid hemorrhage into the verticals, or compression of the basal cisterns on the CT is associated with a poor outcome. An MRI may be indicated when the clinical picture remains unclear after a CT to identify more subtle lesions. Most children with abusive head trauma have a combination of intracranial injuries. Diffuse axonal injury is thought to be present in most children with moderate-to-severe brain injuries. Diffuse axonal injury is typically caused by a fast rotation and deceleration force that causes stretching and tearing of neurons, leading to focal areas of hemorrhage and edema that are not always detected on the initial computed tomography (CT) scan. Subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) that occurs because of tearing of vessels in the pia is considered a marker of brain injury severity. It is present in almost half of children who have a severe brain injury. Subdural and epidural hematomas are the most common types of lesion identified in brain injuries associated with abusive head trauma. Cerebral contusions also occur in about 33% of children with moderate-to-severe brain injuries. These injuries are caused by a direct impact (hitting) or acceleration-deceleration (shaking) forces that cause the brain to strike the frontal or temporal regions of the skull. Intracerebral bleeding or hematoma, caused by contusions or a tear in a parenchymal vessel, occurs in up to 33% of children with a moderate-to-severe brain injury. Three-dimensional reconstruction CT imaging is more specific in detecting skull and rib fractures, but also involves greater exposure to radiation. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast is indicated in children who are unconscious, have traumatic abdominal findings such as abrasions, bruises, tenderness, absent or decreased bowel sounds, abdominal pain, nausea, or vomiting, or have elevation of the AST, an ALT greater than 80 IU/L, or lipase greater than 100 IU/L. |

Initial management of an abused child involves stabilization, including assessing the child’s airway, breathing, and circulation. Airway adjuncts should be used in a child who is not able to maintain an open airway or maintain an oxygen saturation greater than 90% with supplementary oxygen. Oxygenation parameters should be monitored using continuous pulse oximetry with a target of greater than 90% oxygen saturation. Ventilation should be monitored with continuous capnography with an end-tidal CO2 target of 35 to 40 mm Hg. Placement of a definitive airway is recommended in the child with a Glasgow coma scale of less than 9.

The blood pressure should also be monitored, as systemic hypotension has been shown to negatively impact the outcome in a child with a traumatic brain injury. Maintaining a systolic blood pressure of 120 mm Hg has shown to demonstrate improved outcomes in children with brain injuries. If hypotension requires correction, isotonic crystalloids should be administered. Colloidal solutions have not been shown to improve outcomes of brain injury.

The child with a brain injury should also receive serial neurological examinations to identify early onset of elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) and implement subsequent interventions to improve intracranial pressure and reduce metabolic demands. Intervention to reduce intracranial pressure is imperative because the rate of mortality related to brain injury is caused by the elevated intracranial pressure.

Initial bedside interventions to reduce intracranial pressure include:

- Elevate the head of the bed to 30 degrees.

- Determine that the cervical collar (if in place) is not impeding venous outflow.

- Ensure that appropriate analgesics and sedation are administered because pain and anxiousness can increase the intracranial pressure. Opiates and benzodiazepines are frequently used, and neuromuscular blockade may be required to prevent actions that can increase ICP such as coughing, straining, and breathing against the ventilator.

- Hypertonic saline (3%) or mannitol are the common hyperosmolar agents that are used to reduce intracranial pressure.

- Routine hyperventilation in brain injury is not recommended, but in the setting of impending herniation, it remains one of the fastest, short-term methods to lower intracranial pressure.

- Intracranial pressure monitoring may be considered in infants and children with severe brain injury.

- Children with elevated ICP that is unresponsive to other therapies may benefit from barbiturates. These drugs are thought to decrease intracranial pressure by decreasing the cerebral metabolic rate.

- Decompressive hemicraniectomy is a surgical procedure that evacuates a hematoma, but it also is a primary treatment of resistant ICP. Increased intracranial pressure is reduced when part of the skull is removed through a decompressive hemicraniectomy.

- Hypothermia has not been shown to improve outcomes in children.

Once the healthcare provider ensures that the child is stable, a complete history and physical examination is required. Child protective services must be informed of any suspicion of child abuse. Having a child abuse specialist involved during the exam is optimal. If the child is seen in an outpatient setting, there may be a need to transfer the child to a hospital for laboratory and diagnostic testing as well as the appropriate continuation of care. Even if a child is transferred to another healthcare provider or facility, the initial healthcare provider first involved with the child’s care has the responsibility of being a mandated reporter. It is not the responsibility of the healthcare provider to identify the perpetrator, but it is their responsibility to recognize potential abuse. The healthcare provider must continue to advocate for the child by ensuring that they receive the appropriate follow-up care and services.

Likewise, victims of sexual abuse should have their physical, mental, and psychosocial needs addressed. Baseline sexually transmitted infection (STI) and pregnancy testing should be performed as well as empiric treatment for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomonas, and bacterial vaginosis infection. This management is possible if the child presents to a healthcare provider within 72 hours of the abuse to receive appropriate care as well as emergency contraception if desired. Prepubertal children are not provided with the prophylactic treatment due to the low incidence of sexually transmitted infections in this age group. Urgent evaluation is beneficial in children for forensic evidence, who have anogenital injury, who need prophylactic treatment, need child protection, and in those having suicidal ideation or any other form of symptom and/or injury requiring urgent medical care.

New York State Office of Children and Family Services

518-473-7793

http://www.ocfs.state.ny.us/main/

Prevent Child Abuse New York Helpline

English and Spanish

800-342-7472 – 24 hrs.

www.preventchildabuseny.org

New York State Domestic Violence Hotline

800-942-6906 English

800-942-6908 Spanish

www.opdv.state.ny.us

Steps to Report Child Abuse

New York State is divided into fifty-eight local social services districts. The five boroughs of New York City comprise one district. Outside of New York City each district corresponds to one of the fifty-seven counties that make up the remainder of the state. County Departments of Social Services (DSS) provide or administer the full range of publicly funded social services and cash assistance programs. Families whose income meets state guidelines and who meet other criteria, may be able to receive a subsidy to offset some of their childcare costs. Listed below is an alphabetical list of the fifty-eight DSS Offices available throughout New York State.

Albany County DSS

162 Washington Avenue Albany, NY 12210 (518) 447-7300

Website: http://www.albanycounty.com/departments/dss/

Allegany County DSS

County Office Building ·7 Court St. · Belmont, NY 14813-1077 (585) 268-9622

Website: http://www.alleganyco.com/default.asp?show=btn_dss

Broome County DSS

36-42 Main Street · Binghamton, NY 13905-3199 (607) 778-8850

Website: http://www.gobroomecounty.com/dss/

Cattaraugus County DSS

One Leo Moss Drive · Suite 6010 · Olean, NY 14760-1158

(716) 373-8065

Website: http://www.co.cattaraugus.ny.us/dss/

Cayuga County DSS

County Office Building · 160 Genesee Street · 2nd Floor · Auburn, NY 13021-3433 (315) 253-1011

Website: http://co.cayuga.ny.us/hhs/index.html

Chautauqua County DSS

Hall R. Clothier Building · Mayville, NY 14757 (716) 753-4421

Website: http://www.co.chautauqua.ny.us/hservframe.htm

Chemung County DSS

Human Resource Center · 425 Pennsylvania Avenue · Elmira, NY 14902· (607) 737-5309

Chenango County DSS

5 Court Street · Norwich, NY 13815 · (607) 337-1500

Clinton County DSS

13 Durkee Street · Plattsburgh, NY 12901-2911· (518) 565-3300

Website: http://www.clintoncountygov.com/Departments/DSS/index.htm

Columbia County DSS

25 Railroad Avenue · P.O. Box 458 · Hudson, NY 12534 · (518) 828-9411

Cortland County DSS

County Office Building· 60 Central Avenue · Cortland, NY 13045-5590 · (607) 753-5248

Website: http://www.cortland-co.org/dss/

Delaware County DSS

111 Main Street · P.O. Box 469 · Delhi, NY 13753-1265· (607) 746-2325

Dutchess County DSS

60 Market Street · Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-3299· (845) 486-3000

Website: http://www.co.dutchess.ny.us/CountyGov/Departments/SocialServices/SSIndex.htm

Erie County DSS

Rath County Office Building · 95 Franklin Street, 8th Floor · Buffalo, NY 14202-3959 · (716) 858-8000

Website: http://www.erie.gov/depts/socialservices/

Essex County DSS

7551 Court St.· PO Box 217 · Elizabethtown, NY 12932· (518) 873-3441

Franklin County DSS

355 West Main Street, Suite 331 · Malone, NY 12953· (518) 483-6770

Website: http://franklincony.org/content/

Fulton County DSS

4 Daisy Lane · P.O. Box 549 · Johnstown, NY 12095 · (518) 736-5600

Genesee County DSS

5130 East MainSt.· Suite #3 · Batavia, NY 14020-3497· (585) 344-2580

Website: http://www.co.genesee.ny.us/dpt/socialservices/index.html

Greene County DSS

411 Main Street · P.O. Box 528 · Catskill, NY 12414-1716 · (518) 943-3200

Website: http://www.greenegovernment.com/department/socialserv/

Hamilton County DSS

White Birch Lane · P.O. Box 725 · Indian Lake, NY 12842-0725 · (518) 648-6131

Herkimer County DSS

301 North Washington Street ·Site 2110 · Herkimer, NY 13350 · (315) 867-1222

Website: http://herkimercounty.org/content/Departments/View/10

Jefferson County DSS

Human Services Building · 250 Arsenal Street · Watertown, NY 13601 · (315) 782-9030

Lewis County DSS

Outer Stowe Street · P.O. Box 193 · Lowville, NY 13367 · (315) 376-5400

Website: http://lewiscountyny.org/content/Departments/View/30?

Livingston County DSS

3 Murray Hill Drive · Mt. Morris, NY 14510-1699

(585) 243-7300 Website: http://www.co.livingston.state.ny.us/dss.htm

Madison County DSS

North Court St. · P.O. Box 637 · Wampsville, NY 13163 · (315) 366-2211

Website: http://www.madisoncounty.org

Monroe County DSS

111 Westfall Road – Room 660 · Rochester, NY 14620-4686 (585) 274-6000

Website: http://www.monroecounty.gov/hs-index.php

Montgomery County DSS

County Office Building · P.O. Box745 · Fonda, NY 12068 · (518) 853-4646

Nassau County DSS

60 Charles Lindbergh Blvd · Uniondale, NY 11553-3656

(516) 571-4444

Website: http://www.nassaucountyny.gov/agencies/dss/DSSHome.htm

NYC Administration for Children’s Services

150 William St. 18th Fl. · New York, NY 10038 · (212) 341-0900

Website: http://www.nyc.gov/acs

Manhattan Field Office Application Unit

150 William Street – 3rd Floor New York, NY 10038

Brooklyn Field Office Application Unit

1274 Bedford Avenue- 2nd Floor Brooklyn, NY 11216

Queens Field Office Application Unit

165-15 Archer Avenue- 3rd Floor Jamaica, NY 11433

Staten Island Field Office Application Unit

350 St. Mark’s Place- 3rd Floor Staten Island, NY 10301

Bronx Field Office Application

Unit 192 E 151st Street Bronx, NY 10451

Niagara County DSS

20 East Avenue P.O. Box 506 · Lockport, NY 14095-0506 · (716) 439-7600

Website: http://niagaracounty.com/departments.asp?City=Social+Services

Oneida County DSS

County Office Building · 800 Park Avenue · Utica, NY 13501-2981· (315) 798-5733

Website: http://www.ocgov.net/oneidacty/gov/dept/socialservices/dssindex.html

Onondaga County DSS

Onondaga Co. Civic Center · 421 Montgomery Street · Syracuse, NY 13202-2923 · (315) 435-2985

Website: http://www.ongov.net/DSS/

Ontario County DSS

3010 County Complex Drive · Canandaigua, NY 14424-1296 · (585) 396-4060 or Toll Free (877) 814-6907

Website: http://www.co.ontario.ny.us/social_services/

Orange County DSS

11 Quarry Road, Box Z · Goshen, NY 10924-0678 · (845) 291-4000

Website: http://www.co.orange.ny.us/orgMain.asp?orgid=55&storyTypeID=&sid=&

Orleans County DSS

14016 Route 31 West · Albion, NY 14411-9365 · (585) 589-7000

Website: http://orleansny.com/SocialServices/dss.htm

Oswego County DSS

100 Spring Street · Mexico, NY 13114 · (315) 963-5000

Website: http://www.co.oswego.ny.us/dss/

Otsego County DSS

County Office Building · 197 Main Street · Cooperstown, NY 13326-1196 · (607) 547-4355

Website: http://www.otsegocounty.com/depts/dss/

Putnam County DSS

110 Old Route Six Center, Building #2 · Carmel, NY 10512-2110 · (845) 225-7040

Website: http://www.putnamcountyny.com/socialservices/

Rensselaer County DSS

133 Bloomingrove Drive · Troy, NY 12180-8403 · (518) 283-2000

Website: http://www.rensco.com/departments_socialservices.asp

Rockland County DSS

Building L · Sanatorium Road · Pomona, NY 10970 · (845) 364-3100

Website: http://www.co.rockland.ny.us/Social/

Saint Regis Mohawk Tribe Human Services Division

412 State Route 37 · Akwesasne, NY 13655 · (518) 358-2209

Saratoga County DSS

152 West High Street · Ballston Spa, NY 12020 · (518) 884-4140

Schenectady County DSS

487 Nott Street · Schenectady, NY 12308 · (518) 388-4470

Website: http://www.schenectadycounty.com/index.php?page_id=378

Schoharie County DSS

County Office Building · P.O. Box 687 · Schoharie, NY 12157 · (518) 295-8334

Website: http://www.schohariecounty-ny.gov/CountyWebSite/index.jsp

Schuyler County DSS

County Office Building · 105 Ninth Street · Watkins Glen, NY 14891 · (607) 535-8303

Website: http://www.schuylercounty.us/dss.htm

Seneca County DSS

1 DiPronio Drive · P.O. Box 690 · Waterloo, NY 13165-0690 · (315) 539-1800

Website: http://www.co.seneca.ny.us/dpt-divhumserv-children-family.php

Steuben County DSS

3 East Pulteney Square · Bath, NY 14810 · (607) 776-7611

Website: http://www.steubencony.org/dss.html

St. Lawrence County DSS

Harold B. Smith County Office Building · 6 Judson Street · Canton, NY 13617-1197 · (315) 379-2111

Website: http://www.co.st-lawrence.ny.us/Social_Services/SLCSS.htm

Suffolk County DSS

P.O. Box 18100 · Hauppauge, NY 11788-8900· (631) 854-9700

Website: http://www.co.suffolk.ny.us/webtemp3.cfm?dept=17&ID=617

Sullivan County DSS

16 Community Lane · P.O. Box 231 · Liberty, NY 12754 · (845) 292-0100

Tioga County DSS

P.O. Box 240 · Owego, NY 13827 · (607) 687-8300

Website:http://www.tiogacountyny.com/departments/health/social_services/

Tompkins County DSS

320 West State Street · Ithaca, NY. 14850 · (607) 274-5252

Website:http://www.tompkins-co.org/departments/detail.aspx?DeptID=41

Ulster County DSS

1061 Development Court · Kingston, NY 12401-1959 · (845) 334-5000

Website: http://www.co.ulster.ny.us/resources/socservices.html

Warren County DSS

Warren Co. Municipal Center · 1340 State Route 9 · Lake George, NY 12845-9803 · (518) 761-6300

Washington County DSS

Municipal Building · 383 Broadway · Fort Edward, NY 12828 · (518) 746-2300

Website: http://www.co.washington.ny.us/Departments/Dss/dss.htm

Wayne County DSS

77 Water Street · P.O. Box 10 · Lyons, NY 14489-0010 · (315) 946-4881

Website: http://www.co.wayne.ny.us/departments/dss/dss.htm

Westchester County DSS

County Office Building #2 · 112 East Post Road · White Plains, NY 10601-5113· (914) 995-5000

Website: http://www.westchestergov.com/health.htm

Wyoming County DSS

466 North Main Street · Warsaw, NY 14569-1080 · (716) 786-8900

Website: http://www.wyomingco.net/socialservices/main.htm

Yates County DSS

County Office Building · 417 Liberty Street, Suite 2122 · Penn Yan, NY 14527-1118 · (315) 536-5183

Website: http://www.yatescounty.org/upload/12/dss/frameset.html

More informational resources can be found at:

| American Professional Society on the Abuse of Children | This is a nonprofit national organization that focuses on helping professionals get what they need to help abused children and their families. They offer the latest in practices in all disciplines that are related to child abuse. |

| Child-Help USA | Treatment programs such as Child-help Group Homes and Child-help Advocacy centers have been designed to help children who are suffering from child abuse. There are also prevention programs, including Child-help Speak Up Be Safe for Educators. |

| Children’s Safety Network | This program offers resources and assistance to maternal and child health agencies that are looking to reduce violence towards children and reducing injuries that happen unintentionally. There are four Children’s Safety Network Resource Centers that are funded by the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the US Department of Health and Human Services. |

| Darkness to Light | The mission of this program is to empower people to prevent child sexual abuse. It raises awareness of how common child sexual abuse is, and the consequences. Adults are educated so they know how to prevent this type of abuse, as well as recognize it and react appropriately. |

| Healthy Families America | This is the signature program from Prevent Child Abuse America. The national office, which is located in Chicago, IL, offer support, training, technical assistance, affiliation, and accreditation to more than 580 affiliates sites in 38 states, as well as the District of Columbia, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, Canada, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. |

| International Society for Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect | This organization has a mission to prevent cruelty to children in all parts of the world. Cruelty can include sexual abuse, physical abuse, neglect, child prostitution, street children, children of war, emotional abuse, child fatalities, and child labor through the increase of public awareness. |

| Kelso Lawyers | If you need to find more resources about child abuse, Kelso Lawyers can help. They offer resources for victims, such as symptoms of child sexual abuse, reporting abuse, abuse prevention, and causes of child sexual abuse. There are also resources for families, including child abuse statistics and child abuse counselling. |

| National Center for Missing and Exploited Children | This organization offers help to parents, children, schools, law enforcement, and the community to find missing children. It also works to raise public awareness about how to prevent child abduction, child molestation, and sexual exploitation. |

| National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome | The mission of this organization is to help educate parents about the dangers of shaking babies, and to train parents and professionals on the subject. It also conducts research that will help to prevent the shaking of babies. The website is designed to help you find information, answers to questions about this issue, and ideas on how to prevent shaken baby syndrome. |

| Stop it Now | This program was founded by Fran Henry, who survived childhood sexual abuse herself. Her vision was to have sexual abuse of children seen as a preventable public health issue, to help parents focus on the prevention of abuse, and to create programs that are based on these same principles. |

| Administration for Children & Families | www.acf.dhhs.gov The Administration for Children and Families (ACF) is a federal agency funding state, territory, local, and tribal organizations to provide family assistance (welfare), child support, childcare, Head Start, child welfare, and other programs relating to children and families. |

| ACF – Children’s Bureau Express | www.cbexpress.acf.hhs.gov The Children’s Bureau Express is designed for professionals concerned with child abuse and neglect, child welfare, and adoption. The Children’s Bureau Express is supported by the Children’s Bureau, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and published by the National Clearinghouse on Child Abuse and Neglect Information and the National Adoption Information Clearinghouse. |

| Annie E. Casey Foundation | www.aecf.org Since 1948, the Annie E. Casey Foundation (AECF) has worked to build better futures for disadvantaged children and their families in the United States. The primary mission of the Foundation is to foster public policies, human service reforms, and community supports that more effectively meet the needs of today’s vulnerable children and families. |

| Child Abuse Reporting | www.dorightbykids.org Monroe County Health and Human Services maintains a Website dedicated to learning about preventing and reporting child abuse |

| Child Welfare League of America | www.cwla.org The Child Welfare League of America is the nation’s oldest and largest membership-based child welfare organization. It is committed to engaging people everywhere in promoting the well-being of children, youth, and their families, and protecting every child from harm |

| Child Welfare Institute | www.gocwi.org This organization’s mission is to provide information, ideas, and guidance in the field of child welfare training and organizational development consultation. |

| National Children’s Alliance | www.nca-online.org The National Children’s Alliance is a group of 53 national organizations with an interest in the well-being of children and youth. |

| National Data Archive on Child Abuse & Neglect | www.ndacan.cornell.edu A resource since 1988, NDACAN promotes scholarly exchange among researchers in the child maltreatment field. NDACAN acquires microdata from leading researchers and national data collection efforts and makes these datasets available to the research community for secondary analysis. |

| New York State Office for Children and Family Services | www.ocfs.state.ny.us A variety of resource information related to child abuse and maltreatment/neglect specific to New York State. |

| U.S. Department of Health and Human Services | www.os.dhhs.gov |

Child abuse is a public health problem that leads to lifelong health consequences, both physically and psychologically. Physically, children who are victims of abusive head trauma may have neurologic deficits, developmental delays, cerebral palsy, and other forms of disability. Psychologically, victims of child abuse tend to have higher rates of depression, conduct disorder, and substance abuse. Academically, these children may have poor performance at school with decreased cognitive function. It is important for healthcare providers to have a high index of suspicion for child abuse because early identification may be lifesaving. All healthcare providers should report child abuse without hesitation.

When it comes to child abuse, all healthcare providers have a legal, medical, and moral obligation to identify the suspected abuse and report it to child protective services. Many child abuse victims present to health institutions, and healthcare providers are often the first ones to suspect abuse. The key is to be aware of signs of abuse. Allowing abused children to return to their perpetrators usually leads to more violence, and sometimes even death. Even if child abuse is only suspected, the healthcare provider must notify the appropriate personnel and agencies. The law favors the healthcare provider for reporting child abuse, even if it is only a suspicion. On the other hand, failing to report child abuse can have repercussions on the healthcare provider, including litigation and incarceration. The healthcare provider; a mandated reporter, should use the LDSS-2221A form to gather information, and then use it as a tool to organize the information of the abuse while making the call.

If the Statewide Central Register (SCR) of Abuse and Maltreatment accepts the report, the mandated reporter should write down the call identification number given by the Child Protective Services (CPS) Specialist at the SCR. On the upper right corner of the 2221A there is a place to record the call identification number (ID). Two copies of the form, an original and a duplicate must be forwarded to the local CPS agency within 48 hours. A third copy should be kept on file by the reporter.

- NA; (2012). Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents-second edition. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, 13, S1-S2. https://doi.org/10.1097/pcc.0b013e31823f435c

- Adelson, P. D., Wisniewski, S. R., Beca, J., Brown, S. D., Bell, M., Muizelaar, J. P., Okada, P., Beers, S. R., Balasubramani, G. K., & Hirtz, D. (2013). Comparison of hypothermia and normothermia after severe traumatic brain injury in children (Cool kids): A phase 3, randomized controlled trial. The Lancet Neurology, 12(6), 546-553. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70077-2

- ARAKI, T., YOKOTA, H., & MORITA, A. (2017). Pediatric traumatic brain injury: Characteristic features, diagnosis, and management. Neurologia medico-chirurgica, 57(2), 82-93. https://doi.org/10.2176/nmc.ra.2016-0191

- Beaver, K. M. (2017). The interaction between genetic risk and childhood sexual abuse in the prediction of adolescent violent behavior. Biosocial Theories of Crime, 235-252. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315096278-10

- Chen, C., Peng, J., Sribnick, E., Zhu, M., & Xiang, H. (2018). Trend of age-adjusted rates of pediatric traumatic brain injury in U.S. emergency departments from 2006 to 2013. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061171

- Guerrero, M. (2017). Accuracy of PECARN, CATCH, and chalice head injury decision rules in children: A prospective cohort study. The Journal of Emergency Medicine, 53(1), 155-156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2017.05.015

- Litz, C. N., Ciesla, D. J., Danielson, P. D., & Chandler, N. M. (2017). A closer look at non-accidental trauma: Caregiver assault compared to non-caregiver assault. Journal of Pediatric Surgery, 52(4), 625-627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.08.026

- Mucha, A., DeWitt, J., & Greenspan, A. I. (2019). The CDC guideline on the diagnosis and management of mild traumatic brain injury among children: What physical therapists need to know. Physical Therapy, 99(10), 1278-1280. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzz085

- Rooney, E. E., Hill, R. M., Oosterhoff, B., & Kaplow, J. (2018). Violent victimization and perpetration as distinct risk factors for adolescent suicide attempts. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/cgmqv

- Singhi, S., & Kumar, R. (2016). Raised intracranial pressure in children with an acute brain injury: Monitoring and management. Critical Care, 406-406. https://doi.org/10.5005/jp/books/12670_49

- Stockman, J. (2011). Identification of children at very low risk of clinically important brain injuries after head trauma: A prospective cohort study. Yearbook of Pediatrics, 2011, 392-395. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0084-3954(10)79686-x

- Taylor-Robinson, D. C., Straatmann, V. S., & Whitehead, M. (2018). Adverse childhood experiences or adverse childhood socioeconomic conditions? The Lancet Public Health, 3(6), e262-e263. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2468-2667(18)30094-x

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.

To access these Fast Facts, purchase this course or a Full Access Pass.

If you already have an account, please sign in here.